James B. Lansing’s life was a strange mixture of aspiration, turmoil, inspiration, soaring successes and crushing defeats. Nevertheless, his many accomplishments and collective collaborations did much to shape the industry and created the legacy for JBL, the company that bears his initials.

The man we know as James Lansing was born James Martini on January 14, 1902, in the village of Greenridge, Nilwood Township, Macoupin County IL. He was the ninth offspring of 14 children born to Henry Martini, who, reportedly, was born in Saint Louis MO, and Grace Erbs Martini, from Central City IL.

At the time of Lansing’s birth, Greenridge was a village with a population of about 300, with 65 houses, a post office, a store and a school. Its sole reason for being was centered on the coal mine established there in 1894. This was hardscrabble coal-mining country where existence could best be described by the words of Tennessee Ernie Ford’s song, “Sixteen Tons”:

I shoveled sixteen tons, and what do I get?

Another day older and deeper in debt.

Saint Peter don’t you call me, ‘cause I can’t go.

I owe my soul to the Company Store….

Greenridge’s sole claim to fame, if it can be called that, was a labor riot in the area on October 12, 1898, during which 10 people died and the miners union proclaimed a victory in its effort to prevent the company from importing strikebreakers. By 1923, the coal had played out, the mine was closed, the population dwindled, the village was abandoned and the site is now buried under rows of waving corn fields.1

Lansing seems to have had a bent for things electrical and mechanical; at about age 12, he constructed a small radio transmitter with sufficient power to interfere with Naval radio operations.

Henry Martini’s occupation is listed as a coal mining engineer. This most likely was as an engineer in the definition sense of an operating engineer (i.e., ‘One who operates and maintains machinery’), much like a railroad engineer is the operator of a locomotive. If that assumption is correct, it is likely that Henry Martini was a hard-working stiff whose meager wages were stretched thin with 14 young mouths to feed.

At one point, James was sent to board with the Bullough family in Litchfield IL. He adopted that family’s name for his own middle name when he later changed his surname from Martini to Lansing—hence, James Bullough Lansing. Lansing obviously took this seriously, because he had his birth records modified to reflect the name change. It has never been satisfactorily ascertained how he came to adopt Lansing as his last name. Both his brothers, Bill and George, simply dropped the “i” and called themselves Martin. (At the time, it was common for people to change their surnames to sound “more American.”)

Lansing’s Early Childhood

What little we know of Lansing’s early childhood is contained in scraps attributable to his brother Bill’s memory. Bill, who followed his brother James out West, was one of three brothers who survived James. He had gone to work for his brother in the early days of the Lansing Manufacturing Company, stayed on with Altec Lansing after Lansing Manufacturing was bought in 1941, and retired from his job as a tool and dye maker in the metal shop at Altec Lansing sometime in the 1960s.

From Bill’s recollections, we learn that James Lansing completed middle school, attended high school in Springfield IL from which he may (or may not) have been graduated, and took some courses at a small business college in Springfield. James seems to have had a bent for things electrical and mechanical, and the tale is told that, at about age 12, he constructed a small radio transmitter with sufficient power to interfere with Naval radio operations at Great Lakes Naval Center near Chicago. The authorities soon descended, and James’ transmitter was duly dismantled.

Following his natural affinity for mechanics, James sought out employment as an automobile mechanic. This, of course, was long before automotive parts stores existed on every other corner; in those days, if you needed a part, you machined your own. Hence, we can assume that young James became reasonably adept as a machinist. Apparently, his aptitude was sufficient to where his employer, an automobile dealership in Springfield, invested in the tuition to send him to an automotive mechanics school in Detroit.

Seeking His Fortune

Lansing’s mother died when he was 22. No further mention is made of his father, and the young Lansing apparently left home and never looked back. The next we hear of him was that, sometime in 1925, he showed up in Salt Lake City UT. His future wife, Glenna Peterson, tells of their meeting there in 1925, where he reportedly was working as an engineer for a local radio station. By what means Lansing had learned enough about radio to fulfill such a position is not ascertainable; one only can conclude that whatever expertise he may have acquired was self-taught. Then again, this was an era in the early days of radio when conditions, at best, were only vaguely regulated, and “radio engineering” was a barnstorming, learn-as-you-go, fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants pursuit.

Fred Peterson (Lansing’s brother-in-law and one-time employee at Lansing’s manufacturing business) relates that Lansing applied for employment with the Baldwin Loudspeaker Company, but his application was rejected. (Baldwin later offered to buy Lansing’s operation, but it was James’ turn to decline.2)

Lansing and Decker hit it off and decided to form a business relationship. It was agreed that Lansing would take care of the mechanics and technological side of the business, and Decker would manage the finance and sales activities.

While in Salt Lake, Lansing met another young man named Ken Decker. Apparently, Lansing and Decker hit it off and decided to form a business relationship. It was agreed that Lansing would take care of the mechanics and technological side of the business, and Decker would manage the finance and sales activities. Initially, the new venture was established in Salt Lake City; however, the two young men set out for Los Angeles soon after and, on March 9, 1927, they reportedly registered their new enterprise, The Lansing Manufacturing Company (LMCo).3

As we have seen by examining other enterprises of the time (see “Industry Pioneers #16: Sidney N. Shure: Integrity and Innovation” and “Industry Pioneers #15: E. Norman Rauland, American Industrialist”), the radio-receiver manufacturing business was in full blossom in 1927. Literally hundreds of radio-set manufacturers and radio-kit compilers were clamoring for components to satisfy their eager customers. The avowed aim of Lansing’s company was to produce loudspeakers for that marketplace.

Loudspeaker Construction

Kellogg and Rice at General Electric had just barely introduced their “cone-type” loudspeaker concepts. Initially, Lansing Manufacturing used the now-obscure method of armature-type loudspeaker construction, until about 1929, at which time it began producing field-coil-type cone loudspeakers. The company’s product line was concentrated around “larger” six- and eight-inch diameter devices intended for the luxury console radio receiver market.

The absence of suitable magnetic material and development of magnetizer mechanisms with sufficient strength to magnetize loudspeaker flux densities to make permanent loudspeaker magnets practical for large-scale commercial use would not appear for at least two more decades. Thus, the Lansing devices were focused on field-coil-type assemblies.

Initially, Lansing Manufacturing used the now-obscure method of armature-type loudspeaker construction, until about 1929, at which time it began producing field-coil-type cone loudspeakers.

By 1930, despite the specter of The Great Depression and the general falling off of business in the radio parts industry, Lansing Manufacturing Company was able to eke out a living. The company in those days is described as part of a “cottage” industry. James’ brothers Bill and George joined the company; the family members would form cones and wind voice coils at home in the evenings, and then transport them to the factory for assembly the following day.4

During its formative years, in 1927, the company leased space on Santa Barbara Street, moved to 6626 McKinley Avenue and then settled into a headquarters and manufacturing space that was purchased at 6900 McKinley in South Los Angeles. This location served as home for LMCo during its early rise to prominence in the loudspeaker manufacturing business, as well as the loudspeaker manufacturing location for Altec Lansing until 1951.5

Making Motion Pictures Talk

By the mid-1920s, the novelty of motion pictures had started to fade. Radio broadcasting had captured the imagination of audiences, and the flickering images of silent movies lacked the drama of audio soundtracks. Various schemes had been attempted to “synchronize” the visual images with sound tracks, but the results had been less than sterling. Moreover, movie producers had convinced themselves that sound was merely a “novelty” and that implementation would be a “costly” endeavor.

For the most part, audio accompaniment for the silent screen was provided by itinerant piano players in the “pit” or, in more grandiose cinema palaces, by organists poised grandly at elaborate pipe-organ consoles. In either case, the musical score seldom had much continuity with the film images. Clearly, the motion picture industry was in dire need of a boost in order to sustain and increase its audiences.

When Don Juan opened in 1926 with a completely synchronized musical sound track and was followed by The Jazz Singer (1927), with both music and spoken dialog, the movie industry couldn’t contain itself in the headlong race to equip theaters for sound.

Warner Brothers Pictures Incorporated was the studio that provided the needed oomph to get Hollywood headed down the path to sound. Founded in 1903, the company was comprised of four brothers6, sons of Benjamin Eichelbaum, an immigrant Polish cobbler and peddler. Initially, the Warner brothers were showmen who traveled a circuit in Ohio and Pennsylvania, showing motion pictures. From that beginning, they eventually started leasing theaters, acquiring distribution rights and, by 1913, were producing their own films.

To revive the company’s lagging financial condition, Samuel Warner convinced his brothers that Warner Brothers should investigate the use of Western Electric’s Vitaphone process, which essentially was a sound-on-disk configuration. There were several competing movie-track sound schemes under development at the time, all of which were basically incompatible. (That topic gives rise to a tale of exploits that will have to await a later telling.)

The New ‘Talkies’

The point is that, when Warner Brothers chose to go with the Western Electric Vitaphone system, it got there first and, consequently, is credited with revolutionizing the movie industry. When Don Juan opened in 1926 with a completely synchronized musical sound track and was followed by The Jazz Singer (1927)7, with both music and spoken dialog, the movie industry couldn’t contain itself in the headlong race to equip theaters for sound. In an incredible 15 months between 1927 and 1929, the entire worldwide industry was converted to adapt to the new “Talkies.”8

Western Electric (WE), the manufacturing arm of monolithic AT&T, had the vast resources of Bell Laboratories at its disposal to address the technological issues involved in solving problems relative to recording, reproducing and manufacturing the necessary apparatus. The financial backing of the J.P. Morgan banking interest in New York City didn’t hurt.9 WE quickly outpaced the competition, formed the installation and servicing entity of Electrical Research Products Incorporated (ERPI), and thus was able to dominate the sound portion of the motion picture industry for the next several decades.

Western Electric quickly outpaced the competition, formed the installation and servicing entity of Electrical Research Products Incorporated (ERPI), and thus was able to dominate the sound portion of the motion picture industry for the next several decades.

Obviously, all of this intense activity in cinema sound fostered an attendant spurt in the development of loudspeakers. The watchword was efficiency. A 10-watt audio power amplifier of the time was large, bulky and expensive; a unit of that nature easily could cost in the neighborhood of $10,000 (equivalent modern dollars). Furthermore, the materials and production techniques then available for loudspeaker manufacturing were nowhere near vigorous enough to withstand the application of what might now be considered even “modest” amplifier power.

At the same time, cinema theaters were quite spacious, with the intent of seating audiences numbering in the thousands, and had been built with much more of an eye for aesthetics than acoustics. Maximum acoustic output for minimum electric power input was the prime consideration.

Quite logically, the WE cinema sound system was a direct outgrowth of its previous experiences in sound-reinforcement systems. The first large-scale, commercial application for such systems had been used for addressing the crowd at the March 1921 inaugural ceremonies of President Warren G. Harding, as described in Green and Maxfield’s paper to the mid-Winter convention of the American Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers, Inc., New York NY, Feb. 14-17, 1923.10

Initial Cinema Speakers

In his Guest Editor capacity to the AES Anthology, John K. Hilliard interestingly comments [in part], “The use of the Western Electric PA system by motion pictures for location filming allowed the Western Electric Company’s Hollywood representative, Cal Levinson, to get acquainted with studio executives. He finally convinced Warner Brothers that they should witness a demonstration of some potential sound motion picture equipment that was being developed by the Western Electric Company using…[equipment] as described in this paper.”

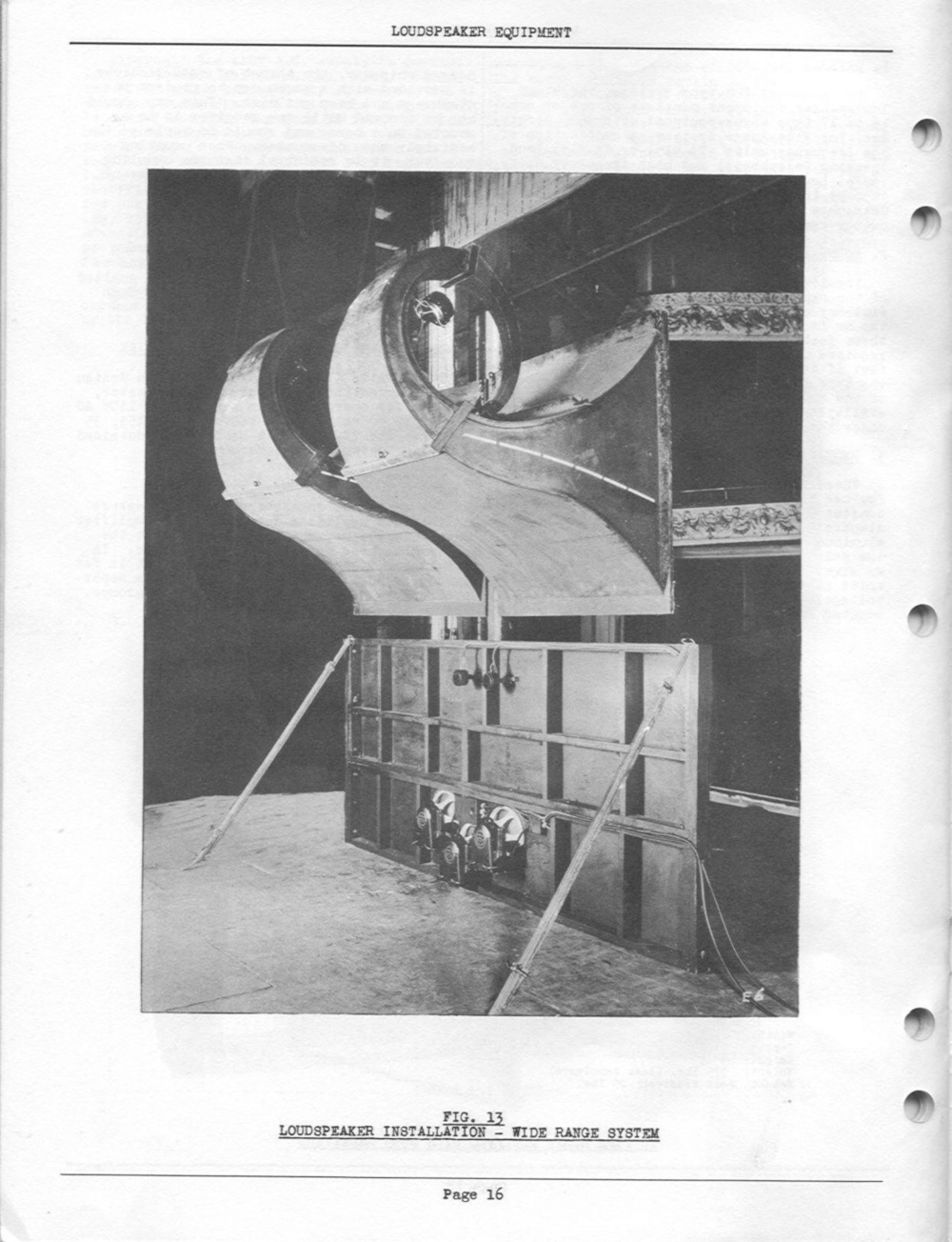

The initial WE loudspeakers for cinema use were “snail” shaped, Model 12A, folded-type exponential horns equipped with the WE-555W compression driver developed by the company’s ever-present, multi-talented resident transducer engineer, E.C. Wente. The system was of the one-way design, having a frequency response in the neighborhood of 100Hz to 5000Hz. Further improvements were forthcoming.

By 1931, the basic WE loudspeaker system had evolved into a three-way system using the “snail” horn and WE-555W driver as the mid-range. Jensen 13 1/2-inch and, later, 18-inch woofers in open-backed (infinite-baffle) enclosures supplemented the lows, and a device known as a Bostwick tweeter extended the high frequencies.

Lansing & The Shearer Horn

The WE assembly had some notable deficiencies. The efficiency and low-end response were restricted by the open-baffle bass drivers, and their distortion was uncomfortably high. Phase discrepancies between the WE-555 and the other driver elements was significant; the 12-foot horn path of the mid-range was so delayed that, in monitoring tests conducted at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios (MGM), a tap dance routine resulted in two taps being heard for every one recorded. About the best thing that could be said for the WE system was that it, far and away, was better than the RCA loudspeakers of the same era; RCA devices used a single eight-inch cone transducer mounted on a straight horn.

Needless to say, MGM was not enthralled with the WE product and set Douglas Shearer11, who was head of the MGM sound department, to affect a solution. Enter John Hilliard, who would play a decisive role in the future of the Lansing Manufacturing Company and the fortunes of that company’s principal.

James Lansing and his designer, Dr. John F. Blackburn, a physics graduate of the California Institute of Technology, likewise became interested in ways to improve on the Western Electric cinema loudspeaker systems. As the story goes, Lansing and Blackburn attended a Society of Motion Picture Engineers (SMPE) show at the Knickerbocker Hotel in Hollywood where Western Electric was demonstrating its “Wide-Range” theater system. They noted some of the obvious deficiencies in the system, and Lansing began making notes about how the system could be improved.

Blackburn related what he and Lansing had observed at the recent SMPE show and their thoughts about how loudspeakers could be improved. With those discussions fresh in mind, Hilliard approached Shearer and outlined how he thought MGM should proceed in the development of its own loudspeaker system.

Not too long afterwards, Blackburn had occasion to meet with his close friend, John Hilliard. At some point, the discussion turned to the poor state of motion picture sound systems. Blackburn related what he and Lansing had observed at the recent SMPE show and their thoughts about how loudspeakers could be improved. The meeting concluded with the idea that Hilliard, MGM and Lansing Manufacturing should get together and discuss the issue further.

With those discussions fresh in mind, Hilliard approached Shearer and outlined how he thought MGM should proceed in the development of its own loudspeaker system. Reputedly, Shearer enthusiastically embraced the proposal and authorized a budget of “any reasonable amount.” It was decided that the MGM system would be of the two-way type and, indeed, it had much in common with the auditory perspective experimental systems developed at Bell Labs (i.e., The Fletcher System).

Hilliard was appointed project leader with the added responsibilities for the design of low-frequency baffles and/or horn alternatives for the bass drivers. A design draftsman on the MGM staff named Robert Stephens12 was assigned to work out the geometry of the proposed multi-cellular horns, and Harry Kimball would work on the crossover designs. It was understood that the Lansing Manufacturing Company would design and deliver the necessary components.

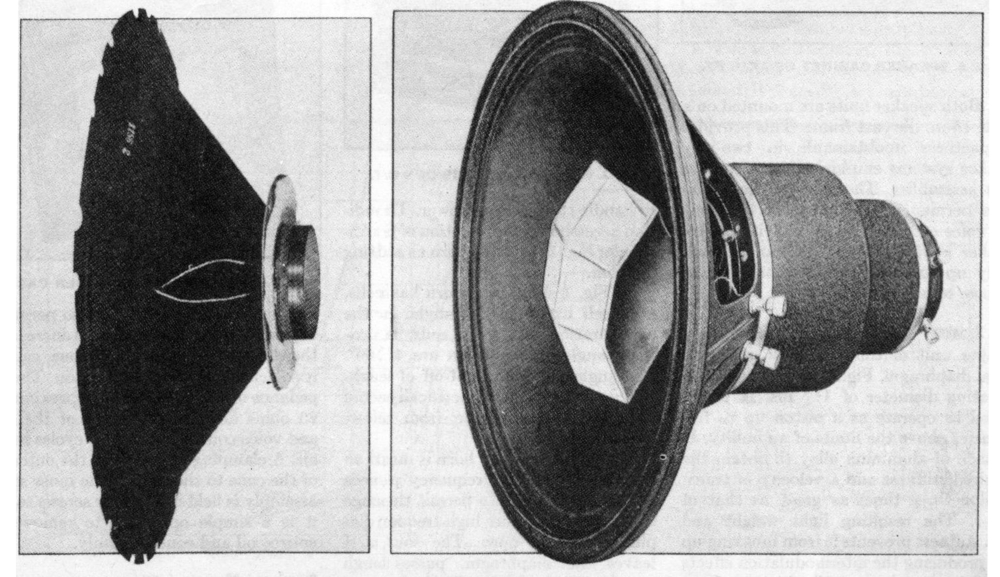

Lansing and Blackburn’s initial endeavor resulted in a rugged, efficient, seamless, 15-inch, paper-cone, field-coil bass driver with a two-inch round-wire voice coil: the model 15XS. This was followed closely by the model 284, a field-coil high-frequency compression driver that used a 2.84-inch flat-wire voice coil attached to a 2.84-inch aluminum diaphragm.

Initially, the 1 1/2-inch-exit-diameter horn throat was equipped with an annular-slit phase plug; however, concerns were voiced that the annular-slit phase plug might be in violation of Bell Labs’ patents. These concerns were later found to be groundless in that Blackburn discovered in the literature that Bell and Tainter had established prior art in the annular-slit phase plug during their earlier work in the area of acoustical phonograph design. Nevertheless, to avoid any patent conflicts, Blackburn devised a radial-slit phasing plug that was used in the production model 284E high-frequency driver.

That the new MGM system would use multi-cellular horns was already an established fact. In Hilliard’s opinion, it was imperative to avoid multiple horn overlaps; hence, individual 17-degree-by-17-degree dispersion cells were configured into composite multi-cellular patterns of two-by-four, two-by-five, three-by-five, etc. The varying patterns thus would be employed in theaters of differing dimensions. Lansing Manufacturing would build the horns, and the LMCo 284E would be the driving element for these devices.

WE, RCA Interest

All the activity at MGM/LMCo couldn’t help but attract the attention of both WE and RCA; both expressed interest in participating. Hilliard continued to work on the bass enclosure design, and his tendency was to employ a straight-horn design. RCA’s Harry Olson stepped forward and suggested they consider one of that company’s folded horns. Not only would the RCA folded-horn design be more efficient, but its reduced size in depth also lent itself to better placement behind projection screens. Thus, the Shearer Horn would become a horn-loaded system for both the high- and low-frequency elements.

The Shearer Horn would become a horn-loaded system for both the high- and low-frequency elements. By 1935, a prototype had been constructed using four LMCo 15XS bass drivers in a re-entrant, low-frequency horn with a single multi-cellular driven by one LMCo 285 driver. It proved to be an unqualified success.

By 1935, a prototype had been constructed using four LMCo 15XS bass drivers in a re-entrant, low-frequency horn with a single multi-cellular driven by one LMCo 285 driver. It proved to be an unqualified success. Testing showed that the bass horn configuration contributed to the overall system design efficiency by as much as 50%. The low-frequency bass horn sensitivity so closely matched the high-frequency that only 2dB of shelving was required to balance the elements.

Frequency response of ±2dB was achieved over a bandwidth of 50KHz to 8KHz. Moreover, by careful mechanical alignment of the HF (high-frequency) and LF (low-frequency) drivers, the relative delay between the HF and LF sections was held to less than one millisecond. The design was significant enough to earn it the Technical Award for 1936 by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

MGM built 12 units for testing in its Loews’ Grand Theatre Circuit and subsequently ordered 75 units each from both WE and RCA. RCA subcontracted with LMCo for its bass and HF compression drivers. Curiously, LMCo was not a recipient of a contract for any of MGM’s original order.

It has been suggested13 that MGM could not, or would not, enforce intellectual property rights to the Shearer design, thereby clearing the way for LMCo to sell its product throughout the entire movie industry. Lansing was the only manufacturer to use the term Shearer Horn; WE used the trade name Diaphonic, and RCA systems were branded Photophone. In the long run, more prestigious theaters and studio screening rooms would use the Lansing system than any of the competing designs.

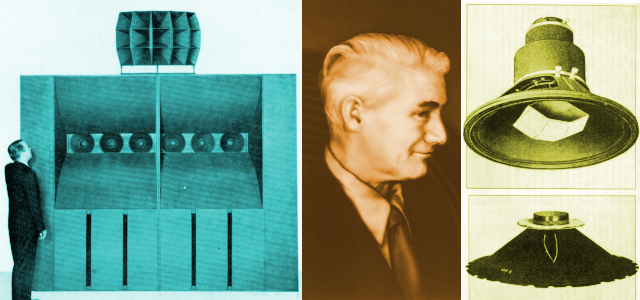

Lansing’s Iconic System

As previously noted, prior to LMCo’s involvement in MGM’s Shearer project, the company had been primarily a supplier of OEM loudspeakers for radios. Lansing’s appetite was whetted for additional applications where the expertise and products that had been developed for the movie industry could be further employed.

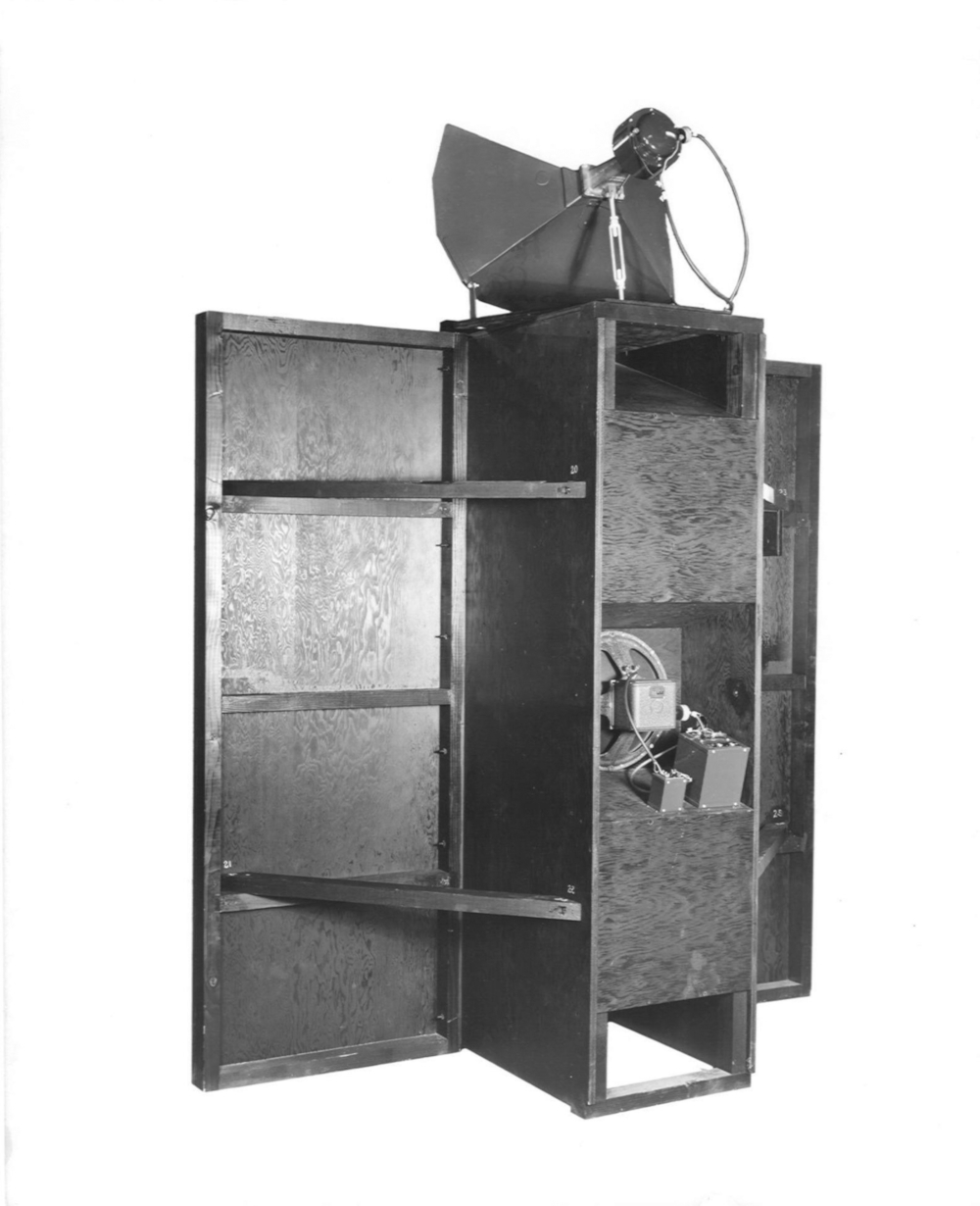

Not too surprisingly, Lansing turned his attention to playback monitoring systems. The first such system was a scaled-down version of the Shearer Horn that used one, rather than four, 15XS bass drivers in a smaller “W” horn enclosure and the 285 compression driver—albeit on a much smaller multi-cellular horn. It quickly found favor for use in movie and phonograph recording studios and general sound-reinforcement application in venues too small to accommodate full-sized Shearer Horns. Despite its popularity, the 500 Monitor System was still much too large for use in physically smaller spaces.

Lansing and Blackburn turned their attention to developing a loudspeaker system that would have the sonic attributes of the Shearer Horn but with a smaller footprint. The resultant system, the Iconic, was an instantaneous success.

Lansing and Blackburn turned their attention to developing a loudspeaker system that would have the sonic attributes of the Shearer Horn but with a smaller footprint. The resultant system, the Iconic, used a bass reflex cabinet, a new 15-inch bass driver and a smaller-format compression driver mounted to a diminutive 4×2 multi-cellular horn, all of which were crossed over at 800Hz using 12dB per-octave slopes. With its outstanding (for its time) ±2dB response and 40Hz to 10,000Hz frequency response, the Iconic was an instantaneous success.

Ironically, the Iconic helped seal the fate of the Lansing Manufacturing Company. It was said that Altec’s decision to acquire James Lansing’s company was due, in part, to George Carrington’s high opinion of the Iconic.

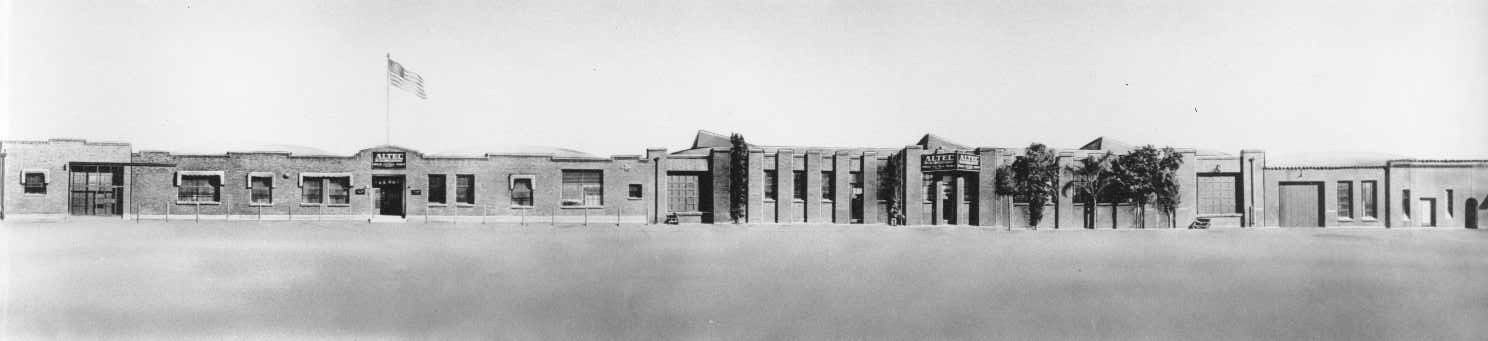

Altec Acquires Lansing

Two totally unrelated but significant events allied to shape the direction of the Lansing Manufacturing Company. By 1936, the Great Depression had engulfed the country, and the motion picture industry was not immune. Faced with a declining market share in what was becoming a saturated market for new systems, Western Electric decided to divest itself of ERPI, its far-flung motion picture theater service operation.

A group of ERPI’s engineers, including George Carrington, Mike Conrow and Alvis Ward, perhaps with more faith in their abilities than economic good sense, bought the operation for the sum of $1.00 and founded the All Technical Service Corporation (Altec). Assets of the new company amounted to $23,499.66 in parts purchased from Western Electric and 295 of what probably were the best-trained audio technicians in the industry. Pundits predicted that the new company would last two years.

A group of ERPI’s engineers, including George Carrington, Mike Conrow and Alvis Ward, perhaps with more faith in their abilities than economic good sense, bought the operation for the sum of $1.00 and founded the All Technical Service Corporation (Altec).

In 1939, Ken Decker, Lansing’s longtime business partner, was killed in an airplane crash while serving as a reserve officer pilot with the Army Air Corps. As long as Lansing would consent to stay in his lab and out of the front office, Decker had ably managed the Lansing Manufacturing Company’s business affairs. But, without Decker’s expertise and judgment, the company’s financial affairs quickly unraveled. By 1941, it appeared that only by selling LMCo would Lansing be able to avoid bankruptcy.

In 1938, another factor came into play. Western Electric, under pressure from the US Justice Department, agreed to sign a consent order that, in effect, forced WE to divest itself of any leasing arrangements involving the cinema theater industry.14 Altec had managed to survive largely on the basis of its theater service contracts, but it was apparent that the stock of existing ERPI products would be diminished and a source for new manufacturing items would have to be developed if the company was to achieve any long-term stability.

On December 4, 1941, the All Technical Service Corporation bought the Lansing Manufacturing Company. Terms of the sale were reported to be $50,000 cash. The new entity would be named Altec Lansing Corporation.

Western Electric agreed to license Altec to manufacture all of the proprietary designs that were covered in the consent decree; royalties never were charged by Western Electric for Altec-manufactured items. Now, Altec needed a manufacturing facility.

On December 4, 1941, the All Technical Service Corporation bought the Lansing Manufacturing Company. Terms of the sale were reported to be $50,000 cash. The new entity would be named Altec Lansing Corporation.15 LMCo’s 19 employees would be absorbed by the new entity. James Lansing would assume the title of vice president of engineering, and manufacturing of some LMCo products would continue under the Altec Lansing brand name.

The physical facilities acquired at 6900 McKinley are remembered by some old-timers as being “pretty bleak and a virtual hole in the wall, where packing crates served as desks.”16 Alvis Ward came west from New York to manage the new facility.

Altec Lansing Era

James B. Lansing, relieved of the strain of financial worries, now could devote his energies to developing his creative engineering talents further. From all that we have learned thus far, Lansing was not a “degreed” engineer in the sense that his knowledge had not been acquired through the normal channels of academic higher education. Undoubtedly, Lansing had absorbed considerable knowledge in the areas of basic engineering, magnetics and network design from associates such as John Blackburn, Robert Arnold and Ercil Harrison; however, when it came to production engineering for manufacturing and tooling, Lansing was an undisputed genius.

It takes an uncanny skillset for a tool-and-die man to envision the necessary mirror-image patterns that can be translated into production items. Perhaps because of his early training in machining and his bent for mechanics, Lansing possessed more than his fair share in his natural affinity for tooling. Jim Lansing was one of those rare individuals who displayed commendable talent for figuring out how to make the tooling that would result in the production of products consistently and efficiently.

The Altec Lansing A Series

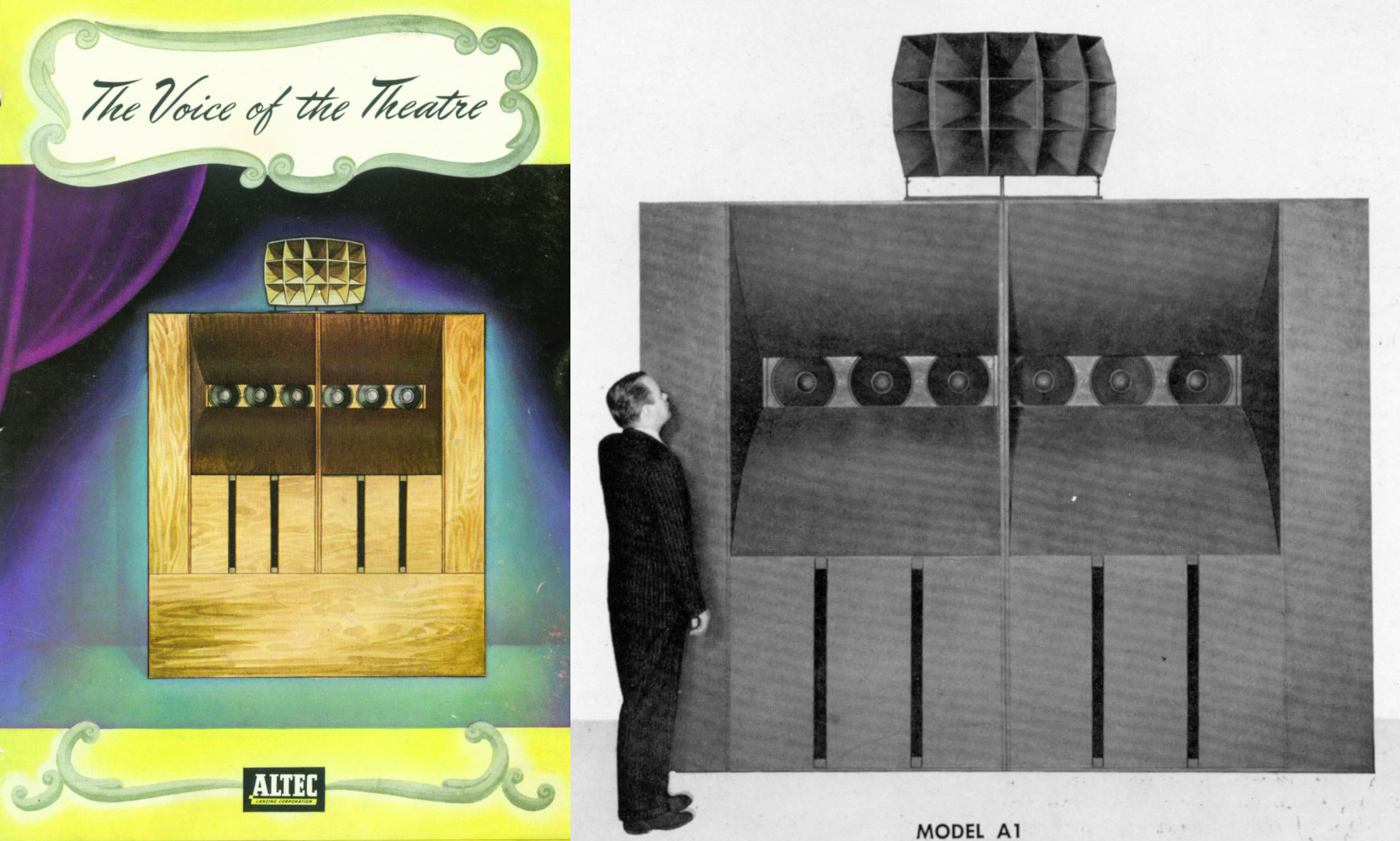

During Lansing’s tenure at Altec Lansing, the company introduced some innovative and forward-looking products, not the least of which was the A-Series of Theatre Loudspeaker Systems that became the leadoff products in the company’s long line of Voice of the Theatre systems. These systems would become the company’s flagship loudspeaker systems and would have preeminence in motion picture theaters well into the modern era.

The A-Series represented the first really new loudspeakers for the theater market since the heyday of the Shearer Horn-designed model by Lansing and Hilliard. It measured some eight feet tall, and with wings attached, it was about 12 feet wide. (As they say in automotive circles and loudspeaker cabinet designs, “There’s just no substitute for cubic inches.”) The enclosed back of the low-frequency section, plus a combination of horn loading in the mid-bass region and porting in the low-frequency range, resulted in a level of low-frequency performance previously unattainable. A new bass driver, the 515, came into existence. Initially, the 515 was derived from the earlier 415 field-coil device (some say inherited, in part, from prior work at either WE or LMCo).

The A-Series of Theatre Loudspeaker Systems became the leadoff products in Altec Lansing’s long line of Voice of the Theatre systems. These systems would become the company’s flagship loudspeaker systems and would have preeminence in motion picture theaters well into the modern era.

When the 515 was released as part of the A-Series in 1945, it was equipped with Alnico V magnets and a three-inch, edge-wound copper voice coil. The high-frequency portion of the two-way also sported a new HF compression driver with a 2.84-inch voice coil, a field-replaceable diaphragm and a low-mass aluminum diaphragm—the 288.

Many of the processes that we consider standard in today’s loudspeaker manufacturing business came into being during those days. In addition to the use of Alnico V, other processes included the high-speed winding of flat-wire voice coils on metal mandrels and the hydraulic forming of high-frequency aluminum diaphragms.

The Altec Lansing 604

Nevertheless, all things were not completely “peaches and cream” in the Altec Lansing Engineering Department. It is reported by several reputable sources that Lansing, Carrington and Hilliard were frequently at loggerheads over any number of issues; an underlying current of resentment clouded Hilliard’s relations with Lansing. To Hilliard’s dismay, Lansing often would halt production while he made improvements. As director of acoustical research and, essentially, the main salesman for Altec Lansing at the time, Hilliard would explode, and the fight would be on.

Nowhere is this rivalry more pronounced than in the circumstances that surrounded development of the Altec Lansing 604 loudspeaker. This is a controversy that still finds proponents of conflicting opinions, and some prejudicial claims for their own particular champion are still evident today.

For anyone not familiar with the 604, it was a two-way coaxial (Altec Lansing used the term “Duplex”) that combined a miniature multi-cellular horn mounted concentrically on a 15-inch woofer with an 801 driver mounted behind and firing along the axis of the system.

To this day, many still consider the 604 to be the epitome of monitor loudspeakers. The product continues to be built in limited quantities and on a custom-order basis even today by Great Plains Audio in Oklahoma City OK.

Reams of Misinformation

Over the years, there have been reams of misinformation regarding development of the Altec Lansing 604. Some have insisted that the 604 had its beginnings in the lab at LMCo, and that tooling for an experimental (601?) existed when LMCo was bought by Altec in 1941. Others maintain that Art Crawford, a prominent radio broadcaster and Los Angeles-area entrepreneur, suggested that Altec Lansing develop such a product. Still others maintain that the 604 was created independent of any prior design. Some swear it was a James Lansing design; others are just as adamant that full credit should go to Hilliard or Carrington. In some circles, Dr. Paul Veneklasen, who has been erroneously reported as being in the acoustic lab at the time, is said to have been slighted, and forever miffed, when he was denied any credit—or even honorable mention—for his contributions.

Research, in connection with the preparation of this article, proves that:

- LMCo never produced a coaxial loudspeaker of any type; James Lansing did no experimental work on any such device.

- The predecessor to the 604 was the field-coil, 15-inch 601 that was produced in limited quantities (about 100 to 150 pieces) and was produced between 1943 and 1945.19

- John Hilliard was a continent away at MIT when the Duplex Speaker was introduced; hence, he could not have participated in the design.

- Art Crawford, indeed, did make suggestions that Altec Lansing pursue the design. In a letter dated May 15, 1951, from George Carrington, president of Altec Lansing, to Crawford, Carrington acknowledges Crawford’s contribution to the design.

- Dr. Paul Veneklasen was not employed by Altec Lansing at the time of the 601-604 development. His dissatisfaction arose from a dispute over credit for the M20 microphone, a later development.

In all likelihood, the 604 probably was the result of several individuals’ combined efforts.

Predecessor to JBL

One of the conditions that Lansing had agreed to when he sold LMCo to Altec in 1941 was that Lansing would not go into business for himself for at least five years. However, promptly with the expiration of the agreement, Lansing left Altec and again struck out on his own.

In a defiant move that he probably should have known better than to attempt, James B. Lansing christened his new enterprise Lansing Sound Incorporated and opened the doors on October 1, 1946. Having sold the name Lansing back in 1941, he immediately ran afoul of his previous employer’s trademarks. An out-of-court settlement resulted in the new company being re-christened James B. Lansing Sound Incorporated.

Initially, at least, the new company essentially was a one-man operation. The corporate letterhead identifying the new headquarters was the offices of his financial consultant. Manufacturing space consisted of a machine shop located in an avocado grove that Lansing owned near the San Diego County town of San Marcos.

Lansing left Altec and again struck out on his own. In a defiant move that he probably should have known better than to attempt, James B. Lansing christened his new enterprise Lansing Sound Incorporated and opened the doors on October 1, 1946. An out-of-court settlement resulted in the new company being re-christened James B. Lansing Sound Incorporated.

Despite being woefully undercapitalized, Lansing commenced designing and producing loudspeaker products. His first product, the D101, was a near carbon copy of the Altec Lansing model 515. In another move that would almost surely ensure drawing the ire of his former employer, Lansing dubbed the new D101 with the trade name Iconic. What he hoped to gain by irritating Altec Lansing is both unknown and baffling. Once again, he found himself facing legal action for violating trademarks that he could ill afford, and he was served with a cease-and-desist order.

Undaunted, he set about designing and building new components that, when assembled, constituted a virtual copy of his original Iconic system. A new high-frequency driver, the D175, inspired by the 801, appeared, and a new 15-inch transducer with a revolutionary four-inch voice coil replaced the controversial D101.

Previously, the idea of producing a four-inch voice coil had been utterly unattainable. The attainability of Alnico V and the availability to procure a reasonably sized magnet from Arnold Engineering Company of Chicago resulted in a device that could be saturated magnetically to about 12,000 Gauss.

Again, Lansing’s tooling and machining skills came to the forefront inasmuch as the four-inch device required a precision in manufacturing that had hitherto been unknown in the loudspeaker manufacturing industry. A 12-inch D131 and an eight-inch D208 (albeit with a two-inch voice coil), both with the same new voice-coil technology, followed on the heels of the 15-inch D130.

Another Aspiration Comes Asunder

From what we have read thus far, it is quite evident that James Lansing did not have a good head for business and, in fact, seemingly could never bring his mind to focus on financial matters. We have seen this pattern time after time in similar cases where clever and talented engineers seemingly are unable to grasp the fundamental concepts of finance. A frequently stated, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, axiom in manufacturing circles is, “Never give an engineer a checkbook.” In this respect, James Lansing was true to form, and his new company was never prosperous under his direction.

Hence, from the onset, James B. Lansing Sound, Inc., was plagued with one financial crisis after another. Lansing was facing a repeat of the calamities that had forced his sale of LMCo some eight years prior. By late 1947, the company was in dire straits. In a desperate move, Lansing sought additional financing from the Marquardt Aviation Company.

From the onset, James B. Lansing Sound, Inc., was plagued with one financial crisis after another. By late 1947, the company was in dire straits. In a desperate move, Lansing sought additional financing from the Marquardt Aviation Company.

The terms of the agreement were somewhat onerous. Marquardt would provide manufacturing space at one of its facilities in exchange for 10% of Lansing’s net sales; Marquardt would have the right to take assignment of Lansing’s account receivables to satisfy any amounts due. Marquardt would lend sums for working capital only to the extent that it did not unduly burden the Marquardt Corporation. Marquardt was given an option for 40% of the James B. Lansing Sound, Inc., stock. And, Marquardt’s treasurer, William H. Thomas, would be seated on the Lansing Company’s Board of Directors.

James B. Lansing Sound, Inc., was shuttled about, first into a Marquardt space in Venice CA and then to another plant in Van Nuys. Financial conditions did not improve. In its second year of operation, the company showed an operating loss of $2,500, and its debt to Marquardt was mounting steadily to the point where it appeared that Lansing would soon lose control of his company and be forced into a position of being an employee for Marquardt.

Suppliers were not being paid; only Arnold Engineering, which was Lansing’s primary supplier of Alnico V, agreed, for whatever reason, to extended terms for payment for materials. In early 1949, the other shoe dropped when Marquardt was sold to General Tire Company; General Tire had no interest in maintaining a loudspeaker manufacturing operation, particularly one with dubious financial conditions.

Lansing’s company was forced to move again, for the fourth time in three years, and found itself ensconced at 2439 Fletcher Drive in Los Angeles. Debts had risen to upward of $20,000 and no sign of improvements in business seemed imminent.

Lansing’s Death

Always a moody individual, Lansing vacillated between short-lived periods of exhilarating enthusiasm and long bouts of extreme depression. Tales are told of how he would toil for hours upon hours until, late at night, he would fall exhausted onto a sofa in the lady’s lounge at the old McKinley Avenue plant until awoken by the first secretary arriving on Monday morning. In public, he could be a very personable individual who could take command of presentations with a good deal of knowledge, sincerity and charm. However, in private or in the company of his own employees, he often was despondent and irritable.

Despite all of Lansing’s hard work and diligence in designing new products, crafting them in impeccable fashion, often with his own hands, the business pressures had to have been heartbreaking as he watched his company slowly sink into financial ruin.

It was Lansing’s habit to retire to his property in San Marcos for weekends. Part of this routine usually entailed a stop by his brother’s house for a visit. On September 24, 1949, he stopped by for his last visit. Driven to his wits end by the state of his business affairs, James B. Lansing drove to San Marcos and hanged himself from one of his avocado trees. He is buried at Inglewood Park Cemetery in South Los Angeles.

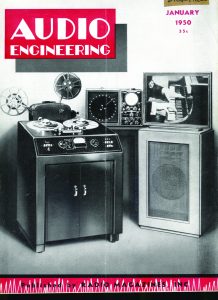

His D-1000 two-way loudspeaker made the cover of the January 1950 Audio Engineering Magazine; unfortunately, he didn’t live long enough to see the issue come to print.

Lansing’s Legacy

Lansing had secured a $10,000 life insurance policy, with his company as the beneficiary. This $10,000, which was a sizable sum in 1949, was sufficient to secure the future of the company.

William Thomas, who had been Marquardt’s overseer of James B. Lansing Sound, Inc., had elected to remain as a vice president and assumed sole ownership of the company. Thomas made the decision to capitalize on the founder’s initials, JBL, to identify the company.

William Thomas, who had been Marquardt’s overseer of James B. Lansing Sound, Inc., had elected to remain as a vice president of the company after General Tire had acquired Marquardt and severed ties with Lansing. Lansing had left one-third of his shares of the company to his wife; by negotiating with Mrs. Lansing, Thomas was able to buy her shares and assumed sole ownership of the company. Further skirmishes with Altec Lansing ensued over alleged violations of trademarks, but most were settled amicably.

Finally, Thomas made the decision to capitalize on the founder’s initials, JBL, to identify the company.20,21 Thus, JBL became the name that we now associate with what is a leading worldwide supplier of loudspeaker and electronic products.

Sidebar: John K. Hilliard (1901-1989)

John K. Hilliard was born in Wyndmere ND. He received his BS in physics from Hamlin University in St. Paul MN in 1925 and a BSEE at the University of Minnesota. He was pursuing his Master’s degree in Electrical Engineering when the lure of Hollywood found him employed by United Artists in 1928. UA, like all the other major movie studios, was in the throes of pursuing the production of audio soundtracks for its films. Hilliard found himself in charge of the recording operations for UA’s first sound picture, “The Coquette.”

In 1933, Hilliard moved over to MGM, where he was assigned to review and recommend changes aimed at reducing the phase shift in audio recording procedures. These investigations culminated in a solution involving the use of audio transformers with very high self-inductance and relatively large coupling capacities. Such devices had been developed by EB Harrison1 at the Lansing Manufacturing Company and, in that way, Hilliard became acquainted with James B. Lansing’s company.

About this same time, Hilliard became aware of some research work being conducted by Bell Labs on the subject of stereophonic reproduction systems—research that ultimately would lead to the Fletcher System (see “Industry Pioneers #3: Dr. Harvey Fletcher And The Rise Of Applied Physics In Audio”). On behalf of MGM, Hilliard approached Western Electric with an eye to having it develop a marketable product using the Fletcher System.

To his dismay, a year later, WE had not made any progress in that regard. MGM made the decision to develop its own cinema loudspeaker system and, under the direction of Douglas Shearer, Hilliard was appointed project manager for the development of the new two-way system. As the accompanying story relates, Hilliard and James Lansing became collaborators on the Shearer project.

Supposedly, it was Hilliard’s acquaintance with George Carrington Sr. (vice president of the Altec Service Corporation [Altec]), and on Hilliard’s recommendation, that Altec was to acquire the Lansing Manufacturing Company. After that acquisition, James B. Lansing and John Hilliard worked with each other in the development of a myriad of products while both were employed by Altec Lansing.

Hilliard became VP of engineering after Lansing left in 1946, a position he would hold until 1960, when he was appointed director of LTV Western Research Center (Altec Lansing then had become a wholly owned subsidiary of LTV). After retiring from LTV in 1970, he entered private practice as an acoustical consultant in the fields of architectural acoustics and noise/vibration control.

On March 21, 1989, he died at his home in Santa Ana CA at the age of 88.

Sidebar: The Enduring Legacy Of The 801

The fabled 801 high-frequency compression driver was developed by Lansing and Blackburn for use in the top end of the Lansing Manufacturing Company’s 1937 Iconic playback/monitoring system. The device used a 1¾-inch aluminum diaphragm, a 4000-ohm field coil, had a one-inch throat exit diameter and was designed to mount to small-format multi-cellular horns and later radial horns.

It remained in production after the All Technical Service Corporation’s acquisition of Lansing Manufacturing in 1941. The 801 was changed to the model 802 after the field-coil version was changed to a permanent Alnico V magnet structure in the mid-1940s and would remain in continuous production by Altec until 1977. After 1977, the magnet was changed to ferrite, and it was re-designated the 902. That driver would remain in production until Telex elected to close the Altec Lansing Corporation in 1998.

Hence, the basic design concept for small-format compression drivers, beginning with the 801 until the demise of the 902, would endure for better than half a century. Its legacy continues to be in vogue in current JBL designs that are essentially outgrowths of Lansing’s 1947-designed model 175, whose inspiration was spawned by the original 801.

Sidebar: Alnico V

Long recognized as a superior material for the construction of permanent magnets, Alnico is an alloy of aluminum, nickel, cobalt, copper and iron. The compound first was developed in Japan in the 1930s for use in permanent magnets. Later developments in the Netherlands, in which the alloy was heat treated in a magnetic field, produced Alnico V. Preceding work using a similar alloy (Permalloy) at Bell Labs in 1916 was used extensively in telephone transmission lines and, particularly, in undersea cables.

An essential component of the Alnico alloy is the compound cobalt. Long known to mankind, traces of cobalt have been found in Egyptian statuettes and Persian beads dating to the 3rd millennium BC; glass from the ruins of Pompeii; and porcelain from the Chinese T’ang dynasty (AD 618-907), where it was used to impart a blue cast to statuettes (envision, if you will, a blue-cast Ming Dog). The Western World rediscovered cobalt when it was isolated by Georg Brandt, a Swedish chemist, in 1735.17

During the World War II years, Altec Lansing was assigned the role of working on a magnetic airborne detector and a submarine-detection system. Because nickel has the properties of changing length when magnetized, it became useful in the production of ultrasonic transducers. Those exploits encouraged the company’s engineering staff to investigate further how such materials could be used for producing permanent magnets that would lend themselves for application as loudspeaker magnets.

Alnico V alloys are very hard and brittle materials, and are extremely difficult to machine. Usually, structures comprised of the material are cast into shape and then subjected to a strict regimen of heat and magnetic treatment before they can be machined into the final magnet product. The combination of producing the precision tooling to machine the structures, the need for the ultra-fine gap required for loudspeaker magnets, and the development of magnetizing machines with sufficient strength to create adequate flux density across the gap had to be overcome before a practical Alnico V magnet could become a reality.

Cobalt, although not rare, is found in small and widely dispersed areas of the world, and sometimes is yielded in traces as a by-product of processing other metals (i.e., nickel, copper, silver and manganese).

As the Canadian nickel mines played down, the concentration of cobalt supplies increasingly were available only from the USSR and Rhodesia. As the Cold War progressed and political instability closed the mines in Rhodesia, the supply of cobalt dwindled and costs escalated. Alnico V for use in loudspeaker magnets was curtailed severely, and ferrite-magnetic (ceramic) magnets became increasingly popular.18

In line with our story, it has to be emphasized that Alnico V magnets required extreme precision tooling. Hence, it can be surmised that James Lansing’s extraordinary talents in creating such tooling was a valuable contribution to the endeavor.

References

1 Audio Heritage: www.rootsweb/~ilmacoup/mines/m_green.htm. [Editor’s note: This link no longer works.]

2 Audio Heritage: www.audioheritage.org/html/perspectives/peterson.htm.

3 Eargle, John, personal correspondence with the author: According to Eargle, his inquiries to the California Secretary of State disclose no record of incorporation.

4 Eargle, John, History of JBL, 1981; www.jblpro.com/history.htm.

5 An interesting collection of photographs taken of the 6900 McKinley plant can be examined at www.audioheritage.org/html/perspectives/6900-mckinley.htm.

6 Harry (1881-1958), president; Albert (1884-1967), treasurer; Samuel (1887-1927); Jack (1892-1978). Whereas Harry and Sam were born in Poland, both Sam and Jack were born in London, Ontario, Canada, and served as managers of the company’s Hollywood Studios.

7 Ironically, Samuel Warner died 24 hours prior to the premiere of The Jazz Singer.

8 The financial rewards were significant. The Jazz Singer cost $500,000 to make; it brought in $2.5 million. Warner Brothers had a net worth of $16 million at the beginning of 1929; when the year closed, that sum had escalated to $230 million.

9 Rival RCA enjoyed the financial backing of the Rockefeller Interests.

10 Green, I.W., and Maxfield, J.P., “Public Address Systems,” Transactions of the AIEE, vol. 42 pp. 64-75 (1923). Reprinted: Sound Reinforcement Anthology, AES pp.A39-50 (1978).

11 Douglas Shearer was the brother of famed movie actress Norma Shearer, a fact that may have had some bearing on Mr. Shearer’s influence with the studio heads.

12 Stephens would go on to found the Stephens Trusonic Company.

13 Audio Heritage: www.audioheritage.org/html/profiles/lmco/shearer.htm.

14 Often the ERPI transaction and the WE consent decree are treated as a singular event, but the ERPI/Altec sale preceded the consent degree by at least a year. WE was precluded from leasing “sound reproduction equipment” to cinemas; however, it would maintain a viable force in the motion picture recording industry (WESTREX) well into the 1950s. (Check the “bug” in the credits of some early 1950 vintage films.)

15 The two words “Altec” and “Lansing” were never hyphenated.

16 Johnson, John W., The Image of Ling-Temco-Voight, 1963.

17 Encyclopedia Britannica, 2005. www.britannica.com/science/cobalt-chemical-element.

18 Audio Heritage: www.audioheritage.org/vbulletin/showpost.php?p=6937&postcount=13. [Editor’s note: Link is to a forum post that requires registration to view.]

19 A paper entitled “The Duplex Loudspeaker,” presented by James Lansing at a SMPE Technical Conference in Hollywood on Oct. 20, 1943, describes the 601 in detail.

20 Eargle, Ibid.

21 Subsequent to Eargle’s 1981 publication, additional research disclosed that the JBL Logo was created by Jerome Gould, a design consultant under contract to JBL. The story of its design and subsequent evolution is sufficient for an article unto itself.

Sincere appreciation is extended to the late John Eargle who, for many years, was the principal historian at JBL; Don McRitchie and Stephen Schell of Audio Heritage; Jerry Hubbard of Fender; and Todd White of Sapulpa OK. Each offered significant contributions and assistance in preparing this article.

This article was originally published in the October and November 2007 issues of Sound & Communications.

Click here for more of Sound & Communications’ “Industry Pioneers” series.