From a modest beginning, Sidney N. Shure’s dedication to excellence, integrity and innovation shaped a manufacturing company whose products exemplified progress in the audio industry.

Sidney N. Shure was born March 27, 1902, in Chicago IL, the eldest son of Bessie and Mandel Shure. His father, a successful merchant in Chicago, instilled in young Sidney the fundamentals of business acumen at an early age. “S.N.,” as Sydney was to become known by his friends and business associates, attended Chicago’s Austin High School and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in geography from the University of Chicago.

Sidney N. Shure’s dedication to excellence, integrity and innovation shaped a manufacturing company whose products exemplified progress in the audio industry.

Like so many of the young men of his era, Shure succumbed to an avid interest in the emerging field of amateur radio, and by age 10 was constructing radio sets from spare parts and kits. Young Sidney’s first official radio amateur license was issued to him at age 11. After graduation from college in 1923, he sought employment with a radio factory in Chicago and followed that endeavor by becoming a salesman for a wholesaler. With an unflagging interest in radio, Shure occupied his spare time by building radio sets for his friends.

Radio fever was sweeping the nation, and S.N. Shure was not immune. In 1922, there were 15,000 radio transmitters operating in the US, almost all manned by amateurs. By 1923, some 5,000 radio parts manufacturers were selling $136 million in parts and radio-building kits. And by 1925, it was estimated that more than three million citizens owned radio sets. The stage for the emergence of commercial radio broadcasting was imminent [see “Industry Pioneers #15: E. Norman Rauland, American Industrialist”]. Although certainly not alone in this realization, Shure, too, sensed the potential in the growing industry of radio.

Religious Influence

At an early age, Shure commenced what was to be a lifelong study of the Talmud.1 He was greatly impressed with the teachings contained in the tract Ethics of the Fathers, and made a commitment to emulate these teachings in his everyday life. “Let the honor of another be as dear to you as your own…if I am for myself alone, of what good am I?…separate not yourself from the community…acquire a teacher for yourself…set aside time for study.” The Ethics became Shure’s automatic response in all his endeavors and encounters. At his eulogy, it was said of him, “His scrupulous honesty, wholehearted loyalty, and dedication to justice and human progress are well known to all who knew him.”2

At a time when intolerance and bigotry were all too common, Shure would not tolerate any ethnic, racial or religious slurs, for in such actions or words he saw only the diminution of the human image.

With these principles as his guiding force, it is no wonder that Shure was to earn the esteem and affection of his employees and associates. From all the writings about the man and from conversations with those who knew him, his sense of fairness and honesty are encountered at every turn. At a time when intolerance and bigotry were all too common, Shure would not tolerate any ethnic, racial or religious slurs, for in such actions or words he saw only the diminution of the human image.

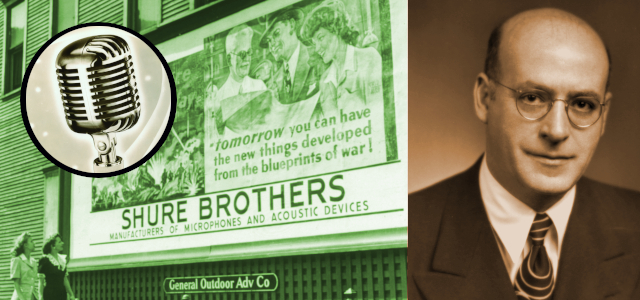

Founding Shure Radio

Sidney N. Shure entered the mercantile marketplace in April 1925 when he founded the Shure Radio Company, operating out of a one-man, one-room office at 19 South Wells Street in downtown Chicago IL—space for which he paid the princely sum of $5.00 per month in rent. It might be surmised that the initial location of the company was something less than ostentatious, inasmuch as the Shure Radio headquarters was described as “a one-room operation that served as the executive office, reception area, stockroom and shipping department.”3 However, that was of little consequence because Shure was the sole executive, receptionist, stockroom clerk and shipping/receiving employee.

Taking a page from the playbook of another venerable Chicago retailing institution, Shure noted that Richard W. Sears had founded the highly successful enterprise of Sears & Roebuck by selling railroad watches to railroad men by direct mail in 1886 and had parlayed that into a highly successful direct-mail retailing operation. Shure commenced producing his own catalog of radio parts and kits. When the first Shure Shots Catalog was introduced in 1926, it was one of only six such catalogs catering primarily to radio enthusiasts that were distributed in the United States.

Sidney N. Shure entered the mercantile marketplace in April 1925 when he founded the Shure Radio Company, operating out of a one-man, one-room office in downtown Chicago.

Apparently, yet another aspect of the Sears operation also caught Shure’s attention. When Sears had formed his company back in 1886, one of his very first employees was a watchmaker to service the company’s wares, a man by the name of Roebuck (hence, Sears & Roebuck). Shure followed suit, and one of his early employees was Harry Lea, who was hired to set up Shure’s Service Department. Lea was to later write, “Shure began with a Service Department. The idea of service was, and is, fundamental…An inferior product is soon discarded and forgotten, and the maker as well. A truly good product that can be properly repaired and serviced…makes permanent friends and customers.”

From these modest beginnings, the Shure Radio Company grew rapidly. By 1928, the fledgling company had 75 employees and had moved to more spacious quarters at 335 West Madison Street. Shure’s younger brother Samuel had joined the company as its first chief engineer, and the company was renamed Shure Brothers Company. Successes piled up, and the parts and accessory business of competitor Hudson-Ross was acquired. The Spring 1929 catalog was chock full of not only radio parts but also electrical fans, electric appliances, luggage, camping goods, novelty furniture and sporting goods. A few scant months later, the bubbling economic enthusiasm of the ’20s skidded to a halt amid the crashing financial chaos that ushered in The Great Depression.

By 1928, the fledgling company had 75 employees and had moved to more spacious quarters. Shure’s younger brother Samuel had joined the company as its first chief engineer, and the company was renamed Shure Brothers Company.

At this point, two factors would forever change the destiny of the Shure Brothers Company. Obviously, the onset of the Depression was devastating, and the company was forced to lay off practically its entire workforce. Younger brother Samuel chose to leave and pursue his vocation, for which his college education had prepared him, in heating and ventilation engineering. The second factor, although perhaps not quite as universally traumatic as the financial crisis, was that the radio parts business was shifting direction.

The Shifting Radio Market

By 1929, it was estimated that there were 16,000 “radio and music stores” in the US, probably far too many to sustain any reasonable expectation of decent margins. Radio manufacturing was no longer confined to hobbyists and part-time tinkerers, but was moving into a mass-production-type marketplace that soon would be selling finished assemblies to consumers through furniture and appliance stores. Of the hundreds of radio manufacturing firms that were founded between 1923 and 1932, only 11 lasted for more than a decade.

By 1929, it was estimated that there were 16,000 “radio and music stores” in the US. Of the hundreds of radio manufacturing firms that were founded between 1923 and 1932, only 11 lasted for more than a decade.

Obviously, Shure was on the horns of a dilemma, and one almost can envision the young entrepreneur musing, “what to do?” For a short period of time, he kept the company afloat by selling parts to the diminishing ranks of radio manufacturers. But this business was dwindling rapidly until, by 1933, a mere nine companies dominated that market, with 74% of radio sales. And profit margins for component wholesalers had been sliced to the bone. Again, we almost can see Shure shaking his head and extolling, “There has to be a better way to make a living.”

Entering The Microphone Market

It was often said of Sidney N. Shure that he was a man who carefully and prudently examined his options before making a firm decision. Consequently, when it was suggested that the company examine the feasibility of producing microphones, the idea came under close scrutiny.

As Jack Berman, who served as sales manager for Shure for many years (and about whom we will hear more later), remarked, “Shure Brothers had commenced an exclusive distribution arrangement with a microphone manufacturer by the name of Ellis Microphones before the crash in 1929. The Ellis devices were rather crude, by and large antiquated, extremely unattractive, and were rather typical of the large, round, spring-suspended, single-button carbon microphones then available in the United States.” Shure became convinced that his company could produce a much better instrument. But could such an improved mic carve a niche in the marketplace?

Microphone manufacturing at the time was dominated mostly by two large suppliers: Western Electric and RCA. E.C. Wente at Western Electric had introduced the first electrostatic (condenser) microphone in 1917, but it had been rejected by the industry as being too cumbersome, and the fact that it required a large external power supply had made the device impractical for anything other than cinema recording purposes.

Western Electric was shifting its emphasis to improving the dynamic (moving-coil)-type microphone. Harry Olson and his team at RCA were beginning investigations relative to combining ribbon technology with dynamic-type mechanisms in order to produce a cardioid-patterned microphone.

Shure became convinced that his company could produce a much better microphone. But could such an improved mic carve a niche in the marketplace?

Directly across the lake from Chicago, in South Bend IN, Al Kahn and Lou Burroughs were engaged in forming a microphone manufacturing firm that would come to be known as Electro-Voice [see “Industry Pioneers # 10: Albert R. Kahn, Founder of Electro-Voice”]. Kahn and Burroughs seemed perhaps to have a running start: Burroughs was an accomplished machinist, and Shure Brothers had never before manufactured a product of any kind. The Europeans, particularly the Germans, were far and away more advanced in electrostatic (condenser) technology. In 1928, Neumann already was producing a commercially viable electrostatic device [see “Industry Pioneers #8: Georg Neumann, Microphone Pioneer”].

Regardless of the fact that the neck-hair on some electronic device manufacturers might bristle, the reality is that it is far easier and less costly to develop and manufacture electronic devices, such as amplifiers and the like, than it is to produce acoustical transducers. The development of an acoustical transducer must, by necessity, be a much more precise science than developing an electronic circuit, and the attendant tooling costs are greatly magnified.

Shure Brothers’ Salvation

Nevertheless, despite the risks in such a venture, Shure became convinced that the salvation of Shure Brothers lay in the development and introduction of a breakthrough microphone product. A long, two-year struggle ensued, during which time a man with lesser fortitude and perseverance might have abandoned the pursuit. It culminated in the introduction of an advanced, two-button carbon microphone. The Model 33N was an attractive bronze beauty with a distinctive profile that quickly caught the attention of recording studios, live performers and sound-reinforcement contractors.

The introduction in 1939 of the Shure Model 55 Unidyne forever identified Shure Brothers with the microphone market.

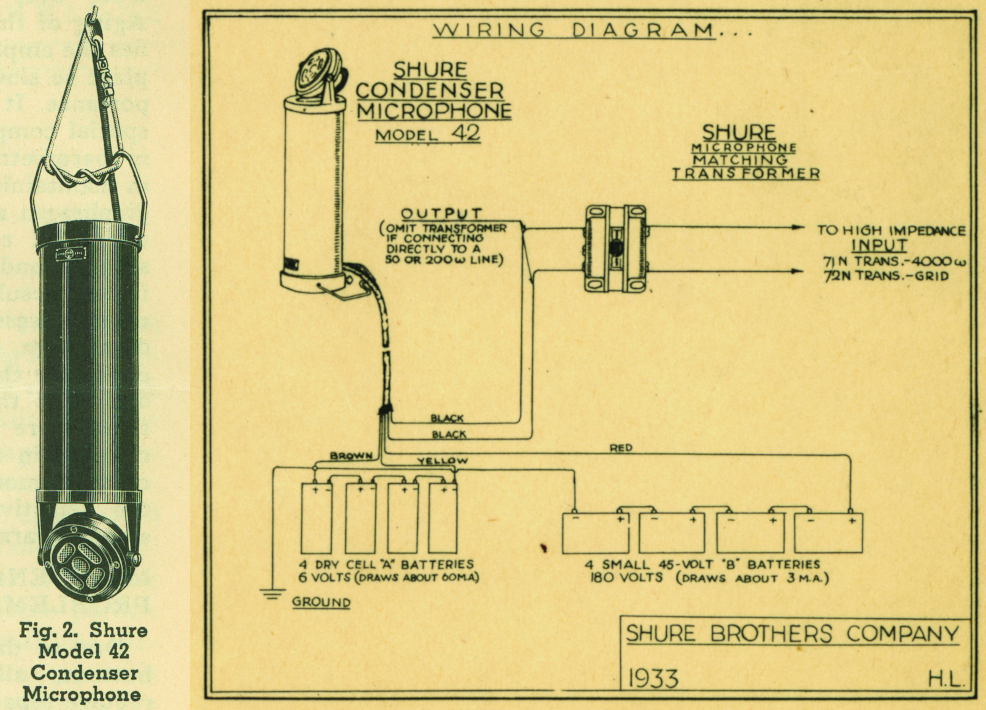

The following year, 1933, saw the introduction of the Shure Brothers Model 42 condenser microphone and a fairly comprehensive line of microphone stands and accessories. Shure Brothers was off and running in the microphone business. Additional successes appeared in the 1930s: In 1935, Shure brought out its first crystal microphone, followed in 1936 with a patented, stylish suspension system for microphones.

However, it was the introduction in 1939 of the Shure Model 55 Unidyne that forever identified Shure Brothers with the microphone market. The breakthrough device developed by Shure’s engineer Ben Bauer was a true single-capsule cardioid, and it set the pattern for every cardioid microphone that followed.

Building A Sales Force

The earlier-mentioned Jack Berman joined the company in 1934. His older brother, Gene, was Shure’s national sales manager, and Jack was one of 17 employees who constituted the reformulated Shure Brothers Company as it entered the microphone manufacturing stage. Jack recalled, “The terms of my employment were such that I would work half my time in the factory for 35¢ an hour and the other half in the office handling correspondence for 40¢. After a week of observing my activities, Mr. Shure drew the conclusion that my typewriter skills were far superior to my mechanical aptitude, and I became a permanent front-office employee.” Jack later became the firm’s second national sales manager, until he left to found the independent rep firm of Jack Berman Company in Los Angeles in 1958.4. Not surprisingly, Shure was one of the Berman Company’s more stalwart principals.

Not content to rest on his laurels and let the “better mousetrap” axiom apply, Shure set out to establish a sales organization consisting of independent sales representatives, each of whom would have a defined geographical territory. These independent businessmen would be responsible for promoting Shure products to stores, radio dealers, recording studios and other outlets.

With his national sales manager, Shure crisscrossed the country by auto, train and bus, working tirelessly to build a sales network that would promote Shure products. By 1936, he had sales representatives in every region of the country, and his products were selling well in several foreign countries. In less than 12 years, and despite some terrible adversities, Sidney N. Shure had built a one-man operation into an international company with a variety of innovative products.

The War Years

When World War II broke out and the US became increasing embroiled in the conflict, the call for military ordnance escalated dramatically. After Pearl Harbor, the entire US industrial capacity was converted to wartime operation; every effort was directed to producing equipment with which the United States and its Allies could counter the Axis forces. The entire American electronics industry was scarcely 15 years old and, with few exceptions, the industry was totally lacking in experience to produce military-grade equipment.5. It was one thing to produce radio sets that would grace the living rooms of consumers and microphones designed for the rarified conditions of recording studios, but a totally different matter to develop and produce electronic products that would stand up to jostling about in tanks on battlefields and in the cockpits of combat aircraft.

The Shure Brothers plant was retooled to meet the military’s demand for rugged, reliable microphone products that could withstand the rigors of use in battles.

The Shure Brothers plant at 235 West Huron Street was retooled to meet the military’s demand for rugged, reliable microphone products that could withstand the rigors of use in battles reaching from the searing desert heat of North Africa to the frigid cold of Siberia. It became an axiom that, “No matter where in the world the military went, Shure equipment would go with them.” In 1942 and 1943, Shure Brothers’ workforce went from 200 to 1200, and a night shift was added as the company strove to keep up with demand.

Formidable Obstacles

Shure and his company faced formidable obstacles. They had to recruit and quickly train a vastly expanded workforce, many of whom were young ladies with virtually no factory production experience. The Engineering Department was called upon to develop vital new products far removed from what the company was familiar with, and production and quality control wrestled with MIL-SPEC stipulations that seemed incomprehensible.

Berman can remember delivering new products to the military and getting them back in pieces. “We never knew what tests the military was using; that was classified. So our engineers just kept developing more and more challenging tests for the products before we would submit them for approval. Eventually, our tests had to be as good as theirs, because nothing was coming back in pieces.” This dedication to perfection was to pay dividends after the war, when Shure elected to continue applying MIL- SPEC procedures as the company returned to civilian production.

Yet another example of Shure’s dedication to principles is borne out by a story told by Lee Gunter, who served as a civilian project manager for the Army Air Corps’ Audio Products Division at Wright Field in Dayton OH. According to Gunter: “Shure had received a contract to develop a small microphone that would work inside the oxygen masks used by bomber crews. Manufacturing was very difficult, and the reject rate at Shure was about 50 percent. I traveled to Chicago and received a briefing on the production process. I could see the tremendous problems they were having and the high costs being borne by Shure. It was a drain on the company. I was concerned that they would be unable to fulfill the contract. But I was told that Mr. Shure was determined to keep up the production, no matter how much it was costing the company, to meet the delivery commitments he had made to the Air Force. So, I decided to stop the line, and within minutes I had a call that Mr. Shure wanted to see me in his office. Now, I had never met Mr. Shure, and he sure was not happy to see me—this fellow who had stopped his production line. He told me that nobody stopped the line. But I told him that, if he could stop production for a week and correct some of the problems, he would reduce rejects to practically nothing and within three weeks he would be back on schedule. He got out of his chair and shook my hand, saying that was ‘the most sensible approach’ he had heard in weeks.”

Unprecedented Consumer Demand

With the cessation of hostilities, the pent-up demand for consumer products was unprecedented. Shure Brothers had seen development of its phonograph cartridges simmer on the back burner during the War Years, and now they came roaring back. In 1946, Shure was the largest producer of phonograph cartridges in the US. A cartridge that could be used interchangeably to play 78rpm and LPs quickly followed. In that same year, the company underwent a corporate change in identification and became Shure Brothers Inc.

In 1946, Shure was the largest producer of phonograph cartridges in the US. In that same year, the company underwent a corporate change in identification and became Shure Brothers Inc.

A perusal at Shure’s “Timeline” in its 75th anniversary book, Sound People, Products, and Values6 provides an encapsulated record of the many accomplishments, innovations, advancements and expansions that the company has undergone from 1932 to 2000. As Shure Inc. reflected back on the occasion of the company’s 80th anniversary in 2005, from its imposing modern facility in Niles IL—a far cry from the humble little offices of the Shure Radio Company of 1925—today’s Shure Inc. must be keenly aware that, behind all of its progress, the guiding wisdom of Sidney N. Shure is most discernible.

Philanthropy And Philately

Despite his busy schedule at the helm of running Shure Brothers,7. Shure took the time to give back to his community and time to devote himself to a range of other personal accomplishments. He and his wife, Rose, funded lectures and visiting professors at Chicago’s Spertus Institute for Jewish Studies and made many philanthropic contributions. Shure himself spent a lifetime pursuing a variety of interests in great depth, including philately, photography, linguistics and psychology.

Another pursuit, aside from his role as a captain of industry, was Shure’s international reputation in philatelic circles. His extensive collection of stamps from the Holy Land was acknowledged to be the undisputed finest display of 19th and 20th century stamps from Palestine and Israel. He founded the Israel-Palestine Philatelic Society in the 1940s, and was active in a number of stamp-collector organizations. To illustrate the esteem in which he was held in such circles, he attained the honored position of a Fellow of the Royal Philatelic Society of London. His extensive collection of stamps of the Holy Land was donated to the National Postal Museum at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC and the Israel Postal and Philatelic Museum, which is part of the Eretz Israel Museum complex in Tel Aviv, Israel.

Shure spent a lifetime pursuing a variety of interests in great depth, including philately, photography, linguistics and psychology. His extensive collection of stamps from the Holy Land was acknowledged to be the undisputed finest display of 19th and 20th century stamps from Palestine and Israel.

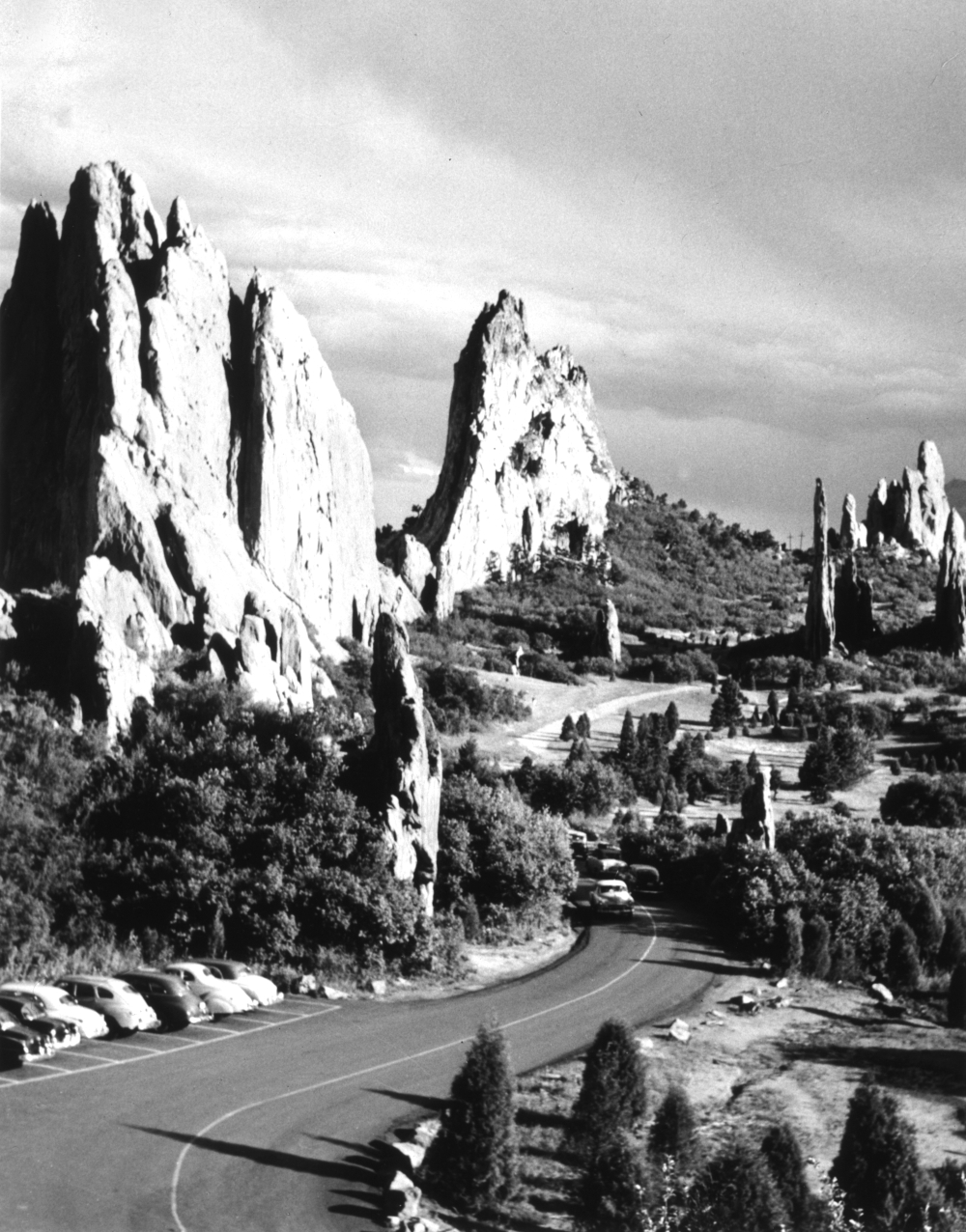

As with everything he did, Shure never took a half-hearted approach. Regarding his avid interest in photography, his son Bob recalled his father’s passion for the art of image-making: “He built a darkroom, studied processing chemistry and did a lot of photographic studies of light on different objects. He considered it a hobby, but he approached it like a professional. As in anything he tried, he wanted to excel at it.” The exquisitely composed photo shown below is a graphic example of the professionalism that Shure extended to his “hobby” of photography.

Shure In Tribute

In 1970, S.N. Shure wrote, “We are concerned on a daily basis with making our company a good place to work, where each person can feel a sense of participation and pride in being part of an organization of integrity and responsibility, an organization of people who respect each other and know that they are serving society by working together to produce the finest products of their kind.”

In some corporate circles, such words might ring hollow as mere platitudes of corporate jingoism. But to those familiar with the operation of Shure Inc., these words embodied the essence of Sidney N. Shure’s commitment to his principles. In the words of his wife, Rose, “He did what he could to make the world a better place.”

Shure passed away at the age of 93 on October 17, 1995.

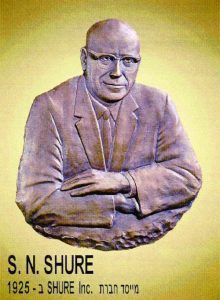

Sidebar: S.N. Shure Honored With Two Israeli Stamps

Two stamps were issued posthumously by the Israel Postal Authority honoring S.N. Shure, as a result of the efforts of Ahinoam Giveon, managing director of Shure’s distributor in Israel, Giveon Electronics. One stamp bears the bas-relief of Shure; the other pictures the Model 55SH Unidyne microphone.

S.N. Shure founded the Israel-Palestine Philatelic Society in the 1940s and was a Fellow of the Royal Philatelic Society in London. He was also a member of the Collector’s Club of Chicago, the Chicago Philatelic Society and the Collectors Club of New York. He received the Grand Award (Hennan Trophy) at the Chicago Philatelic Society’s 64th Annual Exhibition in 1951.

References

- Jewish religious writings.

- Dr. Nathaniel Stampfer, Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies.

- Shure Incorporated, 75th Anniversary Commemorative Book, 2000.

- Berman, Jack, telephone interview with the author.

- At the onset of World War II, the US total defense industrial production was less than 2% of the nation’s production—and electronics was a minuscule portion of that percentage.

- www.shure.com/en-US/about-us/history

- Shure Brothers Inc. was renamed Shure Inc. in 1999.

This article was originally published in the October 2006 issue of Sound & Communications.

Click here for more of Sound & Communications’ “Industry Pioneers” series.