On some—albeit rare—occasions, there appear individuals who are inclined to merge the lofty pursuits of academic endeavor with the more practical applications of science. Such is the case with Dr. Eugene T. Patronis. Although Patronis has spent the majority of his adult career in academia, he seemingly never lost sight of how the practical aspects of his endeavors could be used for the benefit of all. (When this writer inadvertently referred to him as a theoretical physicist, he promptly corrected me and explained why he prefers to be considered an experimental physicist and spurns the title theoretical physicist.)

The Early Years

Eugene Patronis, Jr., was born in Quincy FL on February 26, 1932, the only child of Eugene, Sr., and Alice Mitchell Patronis. A small agrarian, far-north Florida community (located hard against the border of Georgia), Quincy is the county seat of Gadsden County. Historically, it owes its existence to a thriving and once-prosperous tobacco industry that was introduced to the area by Virginia planters in the pre-Civil War era who found the locale quite suitable for the production of cigar-grade tobacco. Another factor that played a prominent role in the community’s development was the transformation of an enterprise called Coca-Cola that, with investments by local citizens, among others, was to grow into a worldwide conglomerate. [Note: An investor in the original offering of Coca-Cola (a $40/share investment) who maintained that holding and reinvested the dividends would now have a net worth of $4.6 million.]

Although Patronis has spent the majority of his adult career in academia, he seemingly never lost sight of how the practical aspects of his endeavors could be used for the benefit of all.

Perhaps it was a combination of growing up in a relatively prosperous rural community, a strong family heritage and the conditioning of living through the hardships of the Great Depression that shaped young Eugene’s development.

Coming of age during the war years (1942-1946) while still a grade-school/high-school student, Patronis found himself exposed to the intricacies of motion-picture technology. In a blog1, Patronis related how, at age 12, he was engaged by one of the local cinemas. He worked his way upward and, due to a war-time lack of qualified participants, found himself being elevated to the position of a projectionist at the Shaw Theatre. This was at a time when handling reels of highly flammable nitrate cellulose 35mm film threaded through a carbon-arc projector could be a risky business.

At age 12, Patronis was engaged by one of the local cinemas. He worked his way upward and, due to a war-time lack of qualified participants, found himself being elevated to the position of a projectionist.

Being an inquisitive youngster, Patronis would take the time between projector changeovers, trimming carbons and reel rewindings to study up on the technical intricacies of cinema operations. At the time, most independent theaters’ projection and sound systems were serviced and maintained by employees of the Altec Theater Service Group (ASC). For the most part, these employees were seasoned ex-Western Electric veterans who had learned their stock and trade in the heyday of 1930s cinema expansions. They were a rushed and harried group with little time to respond to questions from a young aspiring projectionist.

Educational Experience

Patronis makes mention of one particular individual, Robert Albert Passmore, an ASC employee who took the time, and had the patience, to explain to the inquiring young man the technical aspects of how the equipment operated. It was an educational experience for which Patronis was forever grateful.

Robert Albert Passmore, an ASC employee, took the time and had the patience to explain to the inquiring young man the technical aspects of how the projection equipment operated. It was an educational experience for which Patronis was forever grateful.

As World War II wound down, many of the returning veterans were reclaiming the jobs they had left due to conscription into the military. Young Patronis’s role as a projectionist evaporated as a result, and the war-time suspension of hiring under-aged employees was rescinded.

Prior to his theater experiences, Patronis had a chance encounter with John Calloway Byrd, a field technical repairman (lineman) for the rural telephone company. This encounter expanded his education in things pertaining to electronics and communication apparatus. Byrd took kindly to his young protégé and proceeded to teach Patronis the essential elements of maintaining and repairing telephone transmission lines and associated apparatus. Such essentials included how to climb poles, string wire on rural telephone-line construction, repair phones and, eventually, how to splice multi-pair cable.

Prior to his theater experiences, Patronis had a chance encounter with John Calloway Byrd, a field technical repairman (lineman) for the rural telephone company. This encounter expanded his education in things pertaining to electronics and communication apparatus.

The young Patronis trailed along behind his mentor and peppered the ever-patient Byrd with incessant questions related to telephone technology. Today, of course, it is almost inconceivable that a just barely teenage boy could be provided the opportunity to gain this type of hands-on experience.

A year or so later, Byrd introduced the boy to Fred Kibilka, who became the telephone plant engineer. Kibilka taught the boy about the instrumentation used for level measurements on local and long-distance lines, as well as other aspects of telephone inside-plant operation. Patronis grew to always treasure the generosity of these men in sharing their knowledge, along with their friendship.

As a result of intense self-study and lots of trial and error, Patronis was soon able to construct radios from kits, and eventually he could design and construct unsophisticated mixer-power amplifier combinations for use in public address systems that he rented out for extra income. Temporarily suspended from his job as a projectionist, Patronis, who was little more than a boy at the time, continued his technical pursuits by repairing radio receivers and renting his public address systems until he could be rehired by the theater at age 16. Once rehired, Patronis continued to work at the theater until the end of summer, when he left for college to pursue a PhD in experimental physics.

Byrd introduced Patronis to Fred Kibilka, who taught the boy about the instrumentation used for level measurements on local and long-distance lines, as well as other aspects of telephone inside-plant operation. Patronis grew to always treasure the generosity of these men in sharing their knowledge, along with their friendship.

These early experiences in his engineering education left a deep impression on Patronis. When the boy became a man, he felt obligated to always pay the generosity he received from his mentors forward in memory of those who had contributed so selflessly to his own desire to learn.

Patronis Enters Academics

In 1951, commencing with a position as an Instructor at the Southern Technical Institute in Chamblee GA, Patronis then moved on to the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech), where he attained a BS in Physics in 1953. Climbing ever upward, he held a position as a Laboratory Assistant/Instructor at Georgia Tech and as a Research Associate at Brookhaven National Laboratory (1952-1958). Moving back to Georgia Tech, he became an Assistant Professor of Physics (1958-1962) and acquired his PhD in Physics in 1961. Under his mentors, Dr. Charles Braden and Dr. L. D. Wyly, his doctoral thesis was based on the subject of fluorescence yield measurements.

As a result of intense self-study and lots of trial and error, Patronis was soon able to construct radios from kits, and eventually he could design and construct unsophisticated mixer-power amplifier combinations for use in public address systems that he rented out for extra income.

From that date forward until current times, Dr. Patronis has always been a fixture in the Physics Department at Georgia Tech, moving successively from Assistant Professor to Associate Professor to Professor and, ultimately, to Professor Emeritus (his position at the time of this writing.)

During his steady climb up the steps of academic excellence, Dr. Patronis never lost sight of his role as being an instructor and mentor to his students. Many of his students who are now active in the AV Industry can testify to his success in adhering to his principles. A few samples might suffice:

D. Wayne Lee, a Patronis student, a graduate of Georgia Tech and now a successful acoustical consultant in the Atlanta Area, had this to say: “I was a B student, at best, at Georgia Tech, but must have shown a passion for audio and acoustics because Dr. P. kept directly working with me to both keep my grades and my spirits up. He became my mentor and good friend and, still today, is one of my professional heroes. At the 2008 Atlanta SynAudCon Digital Workshop, I asked why he stuck with me, and he said he could spot a gem in the rough. Some just take more polishing than others!”

Patronis became an Assistant Professor of Physics at Georgia Tech (1958-1962) and acquired his PhD in Physics in 1961 under his mentors, Dr. Charles Braden and Dr. L. D. Wyly. From that date forward until current times, Dr. Patronis has always been a fixture in the Physics Department at Georgia Tech.

Lee continued, “As a teacher, Dr. P. has a knack for recognizing if you understand his lecture. When he sees you may not be comprehending, he can lower the level of complexity in the subject and keep trying until he sees that you get it—ll this without being impatient or condescending. Don Davis used to often compliment Gene on this skill. He taught us to take large problems and break them down into smaller, manageable problems to get there.”

Lee was also to comment, “On a personal note, once while in school, he said to me, ‘Your career and work is just something to keep you busy while you are not with your family, friends and loved ones, enjoying life.’ I felt that odd for such a driven person in his esteemed position, talking to a college student trying to reach for a career. And I have never forgotten the comment.”

Charlie Hughes, who this writer first met when he was a transducer engineer at Peavey, and who now operates an acoustical consulting firm in North Carolina, chimed in with these remarks: “Doc is a great teacher. He has the ability to explain difficult material in a way that is more easily understood, many times relating it to practical, real-world situations. He is also a very generous person. When I have contacted him over the years to seek advice or to review some work, he has always been very helpful without hesitation. Mentors, and people in general for that matter, don’t come any better than Gene Patronis.”

Acoustical Transducer Contributions

Dr. Patronis has a wide range of interests that extended from nuclear physics to practical solutions for application in architectural acoustics; however, he seemingly also had a special interest in the development of acoustical transducer (loudspeaker) devices. He contributed greatly in that rather specialized pursuit, and many of his concepts have enhanced that field of endeavor.

These early experiences in his engineering education left a deep impression on Patronis. When the boy became a man, he felt obligated to always pay the generosity he received from his mentors forward in memory of those who had contributed so selflessly to his own desire to learn.

On frequent occasions, he was called upon to contribute his expertise to the refinement of commercial products. Some were transformed into instant practical (marketable) products, while others became laboratory curiosities awaiting further development. An example of the latter progression is contained in the remarks from Tom Danley of Danley Sound Labs, who successfully adapted some early Patronis concepts into successful commercial products. Danley had this to say with regard to his dealings with Dr. Patronis:

“My first contact with Dr. Patronis was in the late 1980s when I worked for a small NASA contractor working in acoustic levitation. While there, I had developed a motor-driven subwoofer called a Servodrive, and it was back then that Gene called with a fascinating application for those speakers. Gene was developing a ‘battle-field noise simulator’ for the Army at Aberdeen MD. I guess, in today’s view, this would be considered a large ‘home theater system’ in a concrete bunker that could produce realistic sound levels.

“I had an interest in ‘loud sound’ (acoustic levitation used in the shuttle experiments required >155dB), but it was fascinating to hear about how [Patronis] had measured the sound of Howitzer shells impacting, and the mind-boggling levels he needed to produce to simulate the event. They ended up using a bunch of our subwoofers for the low-end part of that system, and although I never got to hear it, I wasn’t all that keen to, either, as it actually caused shell shock, just as they desired.”

Dr. Patronis has a wide range of interests that extended from nuclear physics to practical solutions for application in architectural acoustics; however, he seemingly also had a special interest in the development of acoustical transducer (loudspeaker) devices.

Danley continued, “I was not fortunate enough to have had Gene as a professor, but later on, I did attend a number of his presentations and was impressed with how capable he was in explaining something I didn’t understand…like the S-plane view. Not only did I understand his explanation while his voice hung in the air, but much of that stuck well past the point where he stopped speaking about it. I remember thinking what a great teacher he would be and how much I wished I could understand things anywhere near that precisely.

“When he was a presenter at AES and SynAudCon, I heard about his Pataxial loudspeaker, a coaxial horn system. Although my world was still limited to 100Hz and lower, I thought it was an interesting design, and it was the first time I was aware of the need to control the low-frequency radiation angle in commercial sound. It was a later examination of the up and down sides of the conical horn that would germinate and then sprout about 15 years later, leading to the horn designs we currently sell at Danley Sound Labs.”

Danley added, “Doc, like many of the folks I admire, did not suffer fools well; personally, I find that honesty refreshing and something we lack in our PC society now. At the same time, and for the same reasons, I felt some significant apprehension when I posed a more recent acoustic problem to him. It was definitely a ‘wild idea’ and something I could not work out in my mind, but was also too elaborate to easily take the next step and build an experimental prototype. Sitting on the floor in his living room, I drew pictures and waved my hands around, explaining my idea. He was very open to the idea, and to my great relief, he did not shoot it down instantly or say anything that would have shattered my eggshell-like self-confidence. Instead, he asked more questions and, at the end, said, ‘Umm…this is really interesting; let me think about it for a bit.’ Late the next day, he called and said, ‘This is interesting, Tom. You really need to build one to see, take some measurements, see how large the effects are and let me know how it goes.’”

On frequent occasions, Patronis was called upon to contribute his expertise to the refinement of commercial products. Some were transformed into marketable products, while others became laboratory curiosities awaiting further development. Tom Danley of Danley Sound Labs successfully adapted some early Patronis concepts into successful commercial products.

“Anyway,” Danley concluded, “Gene is one of the people that impacted my life, the entire audio industry, as well as his many students. In my case, he is someone I think of as being one in a small number of audio luminaries that are my audio heroes, and I consider myself lucky to have known him. For what it’s worth, he is also a very good shot with a pistol.”

Other Accomplishments

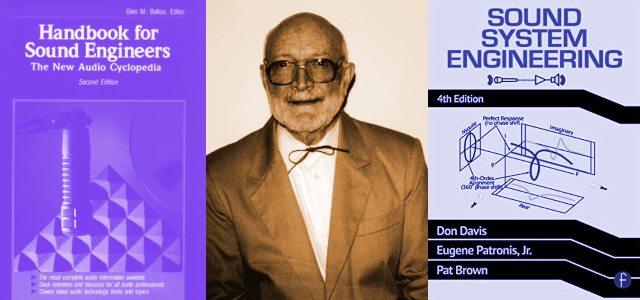

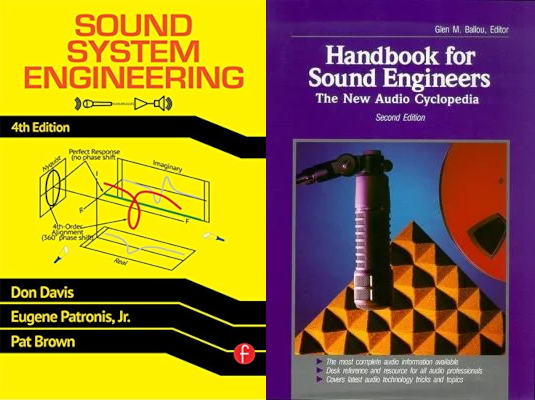

Dr. Patronis’ contributions to the literature pertaining to the AV industry have been extensive. He has been a contributor and sometimes coauthor to a number of technical treatises. He was a major contributor to “The New Audio Cyclopedia, 2nd Edition” and a coauthor, along with Don Davis, in the many “Sound System Engineering” revisions. His list of publications, papers and seminars is lengthy and covers an extensive range of subject matter.

A much sought-after speaker at AV industry events, Dr. Patronis always brings a breath of fresh air into such proceedings. From this writer’s perspective, my first encounter with Dr. Patronis was in 1985. I had just joined the newly reorganized Altec Lansing Corp. when he addressed The Green Club (an assembly of top-tier Altec contractors) just after Altec Lansing’s emergence from bankruptcy. In a much-welcomed, down-to-earth address, Dr. Patronis did much to revitalize those whose support would be essential to the continued well-being of the new organization.

Dr. Patronis’ contributions to the literature pertaining to the AV industry have been extensive. His list of publications, papers and seminars is lengthy and covers an extensive range of subject matter. A much sought-after speaker at AV industry events, Patronis always brings a breath of fresh air into such proceedings.

Patronis is a member of the American Physical Society, Sigma Xi, the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers and the Audio Engineering Society (AES). He has served in several capacities as an AES member. As of this writing in August 2011, he was nominated for a Fellowship in the AES, a just recognition for his many tireless contributions. (Dr. Patronis received his Society Fellowship Award at the 2011 Fall AES Convention. Unfortunately, due to his wife’s illness, Patronis was unable to personally be in attendance. Charlie Hughes, mentioned earlier, was his stand-in.)

Those of us who have strived in the AV industry for any length of time are appreciative of Dr. Patronis’ work on our behalf.

Sidebar: Typical Cinema Projector, Sound System, circa 1944

With amazing clarity and the application of an exceedingly good memory, Patronis detailed the elements of the projection/sound system installation that he encountered while working at the Shaw Theatre during his time as a projectionist.

He remarked, “The projection and sound equipment for this theater was first-rate for its size. It featured a Western Electric Mirrophonic Sound System consisting of a 91A power amplifier, a 12A power supply, a 25A high-frequency horn with a 555 compression driver and a TA4194 18-inch bass driver mounted in a TA7395A low-frequency horn— all properly signal aligned! The power amplifier’s output stage consisted of a single WE300B operated in pure class A that, under the best of conditions, could output about 10 watts. The power supply had to be well filtered for the power amplifier because of the single-ended class A operation. A separate supply also furnished low-voltage DC for the exciter lamps in the sound heads, as well as a higher-voltage DC for the photoelectric cells also in the sound heads associated with the projectors. The 35mm projectors were Simplex Model E-7 equipped with Peerless high-intensity carbon arc lamps and Western Electric sound heads. The arc lamps were powered by a Hertner motor-generator set consisting of a three-phase AC motor driving a DC generator.”

Sidebar: Patronis’s Patents

Here is a list of some of Dr. Eugene T. Patronis’s patents:

- An Integrated Circuit Frequency Modulation Detector, August 1, 1967

- Acoustic Feedback Detector and Automatic Gain Control, March 14, 1978

- Non-Intrusive General Purpose Film Cue Detector, April 2, 1990

- Cinema Sound System for Unperforated Screens, April 2, 1991

- Acoustic Cup Counter, April 9, 1991

- Audio System with Amplifier and Signal Device, April 28, 1992

- Motion Picture Exhibition Facility, June 30, 1992

Reference

- Patronis, an essay on My War-Time Activities (unpublished) 2010

This article was originally published in the October 2011 issue of Sound & Communications.

Click here for more of Sound & Communications’ “Industry Pioneers” series.