Editor’s Note: Some 20 years ago, when the horrors of the 9/11 terrorist attack were fresh in our minds and across newspaper headlines, Sound & Communications published this piece from Drew Milano, who, at that time, was a sales rep for MetroNorth Marketing, Edison NJ, and who helped install an emergency paging system at the Ground Zero recovery site. Milano is still part of our industry, now working at Solomon Cardone & Associates. We share this piece as part of the nationwide remembrance of 9/11 in its 20th anniversary year.

As a manufacturers rep, it’s not unusual for a contractor to call me and ask for help designing a system—but a system at the World Trade Center (WTC) disaster site, Ground Zero, was something else. The call went out on September 14 to several contractors to install an emergency paging system ASAP at the four outside corners of the collapsed WTC area. There was only a siren on site that, when sounded, warned everyone to move to a safe position. The paging horns would be used to give everyone information about where to go and what to do. Each corner had to cover about 500 feet and be about 1,000 feet from the adjacent corner. The system had to be above the rubble (five stories high!); be able to be heard above heavy equipment, generators, trucks etc.; outdoor rated; wireless and stay out of everyone’s way!

We decided on stadium horns, amps and an encrypted wireless system to be installed at the fire command center and at each corner. I called John King at Telex, only to discover that he and Low Voltage Systems’ (LVS, Fairfield NJ) NJ chief engineer Chris Anzalone were thinking along the same lines.

Ground Zero Intercom

Their design incorporated not fixed encrypted wireless as I envisioned, but a series of encrypted intercom systems that added greater flexibility. They had run the concept past the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which liked the idea along with the generous offer of free labor from LVS, and at manufacturer’s cost from Telex. Of course, FEMA wanted the system “yesterday,” and by necessity the system had to be simple and arrive the day after the approval was given. We received approval on Wednesday, and the Telex equipment arrived at LVS Thursday morning.

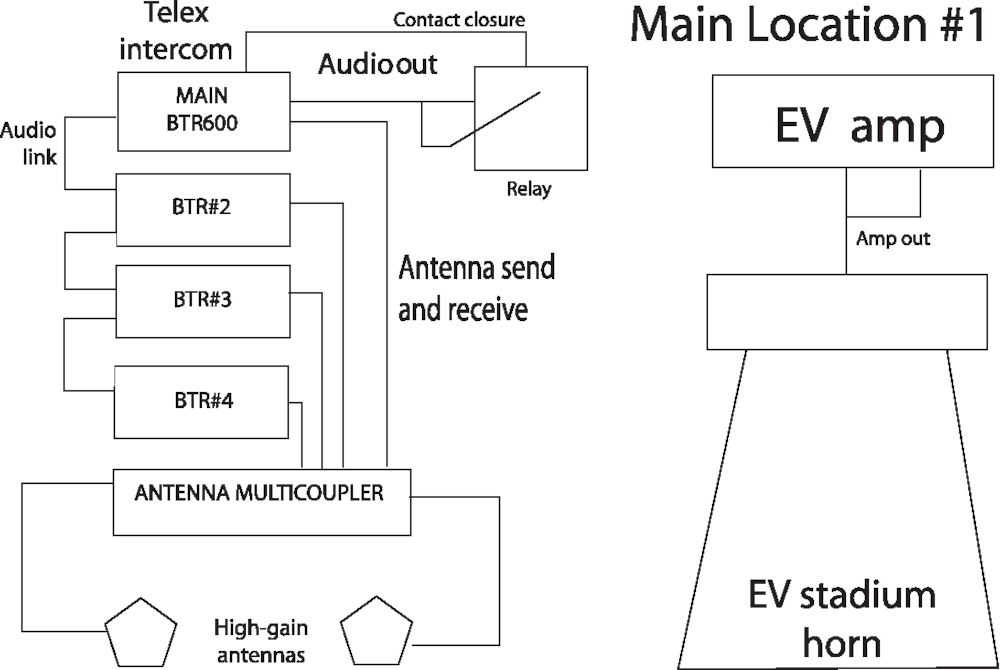

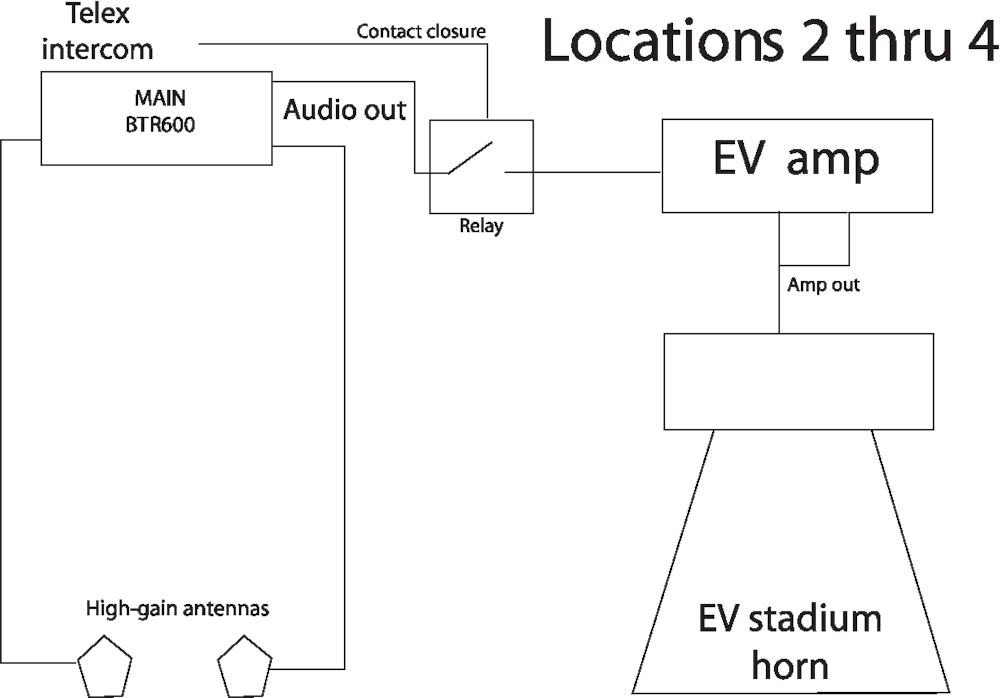

The system consists of four EV MH640 medium-format stadium horns, four EV AP amps, seven Telex BTR-600 wireless encrypted intercom systems and a relay system. The design consisted of a central area #1 for the four intercom wireless base stations, encrypted to prevent unwanted access; an amp; a horn and a relay system to send the audio from the output of the BTR-600 base station to the amp only when Channel 1 of the belt pack talk button is activated. The BTR system is a two-channel, full-duplex intercom offering two-way communication at all times between base stations and belt packs.

The four base stations in area #1 are linked by the unit’s hardwire link ports. “Receive” on base station one sends audio to the other three base stations and closes the contact to send audio to amp/speaker #1. The other three base stations in area #1 each transmit to one of the remaining three speaker locations that have a BTR-600 base, a relay, an amp and stadium horn (see diagram). As well, the second channel of the intercom system was set up so the four belt packs could communicate with each other. The four base stations at area #1 are connected to an antenna multi-coupler with two high-gain antennas and the three satellite locations, each with its own high-gain antenna.

Intentionally Simple Design

The design was intentionally simple because less equipment means less can go wrong, and the system would be running off a generator, in a harsh environment—just how harsh, we were about to find out. Originally, Michael Rogozin, the New York City emergency official and organizer for this project, suggested that we connect to the on-site existing light-pole/generator units for our power. Because there were no site surveys, drawings or details, electricians and carpenters on site were to provide what we needed as we needed it; how the job got done was the result of on-the-spot ingenuity.

The day the project was approved—September 19—we were informed that FEMA would do a background check of everyone going on site. FEMA would send a truck to LVS the next morning to pick up people and all the equipment for the WTC disaster site, and we would not return until the job was done.

When I arrived at LVS the next day, everything was progressing well—but we were in “hurry-up-and-wait” mode. The equipment arrived as promised; we took inventory and checked all the gear, went over the design in detail and got all connectors and cables in place—then waited. LVS’ Anzalone introduced me to installers Al Toledo and Ed Helpeck, who would be on this project; they’ve been working together for 15 years. I got to know a little about these two guys: They did extensive install work in and around the disaster area over the years. In that time, they had become very familiar with the area, the buildings and many of the people, and felt a deep personal need to help in any way.

When the truck finally arrived, we loaded it, and Rogozin drove; the rest of us followed in a car. We received approval to use the Holland Tunnel, closed except for emergency vehicles, with a New Jersey State Police escort to the tunnel approach. Then a US Marshal took us to each of five checkpoints to get to the tunnel entrance, where the biggest loader truck I’ve ever seen was blocking the way. Once it let us through, the Marshal continued to escort us through another three checkpoints in Manhattan before we arrived at the WTC disaster site.

‘It Could Be Raining’

In the movie “Young Frankenstein,” there is a scene where they are complaining about weather conditions and Marty Feldman’s character says, “Well, it could be worse. It could be raining.” That happened to us; when we arrived, it was raining lightly, then started pouring. This turned out to be the worst working conditions I ever encountered. We each were issued a rain suit, hard hat, heavy rain boots and a respirator. We put our rain suits on, unloaded some of the gear onto a hand truck and a cart, and tried to push the gear two blocks over mud, puddles, debris and fire hoses, dodging a constant flow of people and heavy trucks—all the while getting closer to the devastation that’s unimaginable.

Standing at the base of the site, we were looking up at five stories of smoldering debris, twisted metal and concrete, with part of the outer frame of the WTC building still standing, looking like an evil cathedral. Any building still standing, facing the WTC towers, was severely damaged. I was completely disoriented, not recognizing many of the remaining buildings—only the orange spray paint on each building giving its address told me which was which.

While we waited to be told where to go with the gear, we were completely stunned at the site. Reality set in quickly as we got out of the way of heavy trucks and fireman from around the country. At that point, we realized there was no way the gear would survive outside in any kind of box by the generator/light poles, nor could the poles safely anchor the large horns. This left us with finding four buildings where we could mount the horns above the five stories of debris, each with a line of site to the main setup for the wireless system, that were 1,000 feet apart in a square and that would allow each mounted horn to be able to cover a 500-foot area. Add to that: no power, no elevators, no light and an unbelievable amount of dust, debris, metal and broken glass everywhere.

Logistical problems began to mount quickly because we needed to have city project manager Rogozin find the ever-moving fire chief in charge, and the union electricians and carpenters. First we had to know where the fire command station was set up, so we would have line of site for the main four intercom base stations. Then we needed to find three other locations covering the remaining corners, with a direct line of site to these main intercom base stations.

Command Post

We parked some of the equipment out of the rain in the makeshift fire department supply area that used to be a ground-level restaurant on Liberty Street. The fire department took over all the buildings on the street at ground level and made a command post, supply depot and a buffet eatery. A one-story scaffold/cover along the whole block and a tarp kept the rain out. All along this block, tired firemen were packed shoulder to shoulder, sitting on chairs or steps under the scaffolds to rest or sleep, while a never-ending stream of workers filed up and down the only covered, clear-of-debris sidewalk. We dropped the gear inside the depot in a tiny space, and made it our field office.

We had to pick a building that looked central for our needs, get permission to go in and find a window for the speaker and antennas, then install it, get power, hook it up, test it, then move on to the next three locations. This sounds simple enough, and under normal conditions it would take about six hours. No such luck here. The first problem was that Rogozin had to find everyone needed to make this happen. This turned out to be a never-ending problem, and cell phones/walkies not working or batteries going dead didn’t help.

Eventually, we searched a building on Liberty Street, walking up eight flights of stairs in the dark with only a flashlight to guide us, in our rain boots, rain suits, hard hats and respirators, looking for a suitable spot. Although our rain suits were considerably lighter than what the fire department wears, I was exhausted, stripping off anything I didn’t need in the first half hour; how a fireman does it, I have no idea!

Walking through this devastated high-class apartment building, with the occupants’ ruined personal possessions all still in place, was heart-wrenching: children’s toys, family pictures, artwork and clothes, all covered with at least a half inch of dust, and debris on everything.

Up The Stairs

Once we decided on a sixth-floor location above the debris field outside, and with a line of sight to three other potential buildings, the three of us proceeded to carry a stadium horn, amp, four intercom systems, tools, wire, etc., up the stairs in the dark, kicking up dust with our rain boots, all while wearing respirators.

With the gear finally in the desired spot, we tried to connect it by flashlight because the daylight was gone. Where were the electricians and the carpenters? And where was the city project manager? (He was trying to find the others.)

So we continued by flashlight and, as if by magic, there was power. We found some lamps and finished hooking up the gear. A quick test of the speaker and amp proved OK, but the intercom system wasn’t. By the process of elimination, I figured that the antenna multi-coupler wasn’t working and called John King at Telex, who agreed to stay by his cell phone all night. He later confirmed my conclusion: the multi-coupler apparently got wet, and its cooling fan sucked in some dust, so it wasn’t happy about that combination. Actually, neither was I. Taking the high-gain antennas off the multi-coupler and putting them on the main intercom base station, then putting the 1/4 wave whips on the three slave units got us going.

Meanwhile, the carpenters mounted the horn and high-gain antennas by attaching wood to the masonry of the window and the mouth of the horn to the wood with a couple of 2x4s to support the back of the horn. Only the mouth of the horn was outside the window, with the rest sticking into the room. The antennas were mounted on 2x4s stuck out the window and screwed into the masonry of the windowsill. Not a very elegant solution, but it worked just fine.

Full Power

When we were ready to test the system at full power, Toledo went down to ground level with a belt-pack/headset and began “testing 1-2-3,” only to find we didn’t have enough gain to the amp. The intercom has several ways to get audio out, and the hi-Z out was used to match the amp input impedance, but there wasn’t enough gain. So we’d have to use the low-Z output with an impedance transformer.

But right then, the all-quiet signal was given, so testing stopped. The all-quiet signal meant a rescue worker may have heard a possible survivor or saw motion in the debris. It was really strange to hear total quiet after listening to about 85dB of continuous noise. But unfortunately, the all-quiet signal turned out to be for nothing, and we decided to get dinner.

While eating, the city project crew showed up in full force for the first time, at 10:00pm, and they were anxious to get over to the next site. Off we went to scout out the second spot in 2 World Financial Center (WFC), all of us in full rain gear, trudging to meet the fire chief for permission to enter. For reasons I can’t explain, of all the images I saw that day, none left more of an impression than the fire chief. He got his job as chief because his boss was killed when the WTC buildings collapsed into the sub-basement that housed the emergency control center for New York City.

We came up to a group of about a dozen people circled around the chief, who was standing outside in the rain on a pile of rubble that once was the steps to the WFC. Everyone around him had a question or a problem, and there was a constant stream of people like ants marching to an anthill. The chief was in full NYFD gear, heavy coat, pants, boots, helmet, white shirt and tie, standing in the rain, giving commands, pointing and yelling “Next!” With all the confusion, chaos and disaster I experienced that day, in the center of this vortex of activity was only visible sign of stability in the whole mess: the fire chief. I will never look at the Police, Fire or EMS as just a civil service job again!

In Case Of Trouble

The fire chief said OK, we could use the 2 WFC building, with one condition: one person stays outside with a walkie and keeps in contact with the others inside in case of trouble. This was a good safety tip because 2 WFC is a large building that was hit hard. Walking through the thick debris was difficult. We found the stairs in the smaller building on Liberty Street. Reaching the sixth floor left me exhausted, but we went up and down those six flights at least 10 times, carrying equipment. We surveyed the floor and found a suitable window.

Maneuvering around the narrow aisles in this environment was difficult; the typical tight-packed cubicles were filled with chairs and files, along with drop ceilings hanging down, aluminum window frames blown in, broken glass and a lot of debris. The only luxury was the dim emergency lights that were still on. We could see where the firemen broke down several doors with an axe to check for survivors and that they left an orange spray paint slash on every door/room that was checked.

The electricians and carpenters were given instructions, and we all agreed on the course of action for installing the next horn and started for the stairs. Where were the stairs again? Over this way. No over this way. At one point, we found a staircase and went down it with seven people in tow, and then half-way down, the staircase opened up to an area revealing four sets of stairs going in opposing directions! By now, it was around midnight, everyone was tired and nothing looked familiar. After some discussion, we jumped across to the other stairs and continued down, when we discovered several locked doors and one passageway so filled with debris to be nearly impassible. After more discussion, we went back up, jumped to a different set of stairs and down to the bottom to find a boarded-up section we could squeeze through to the outside. This put us about 50 yards away from where we entered, but everyone was happy to be back outside, in the rain—could be worse. We regrouped and decided to call it a day; this last adventure was a clear indication of how tired we were and the dangers involved.

Once I was home, my wife was happy to see that I was OK, and even though it was 2:00am, I had to take a shower to get the filth and stink off me. When my three-year-old son woke me at 7:00 the next morning, my wife tried to shuffle him away so I could sleep, but I got up; I was real glad to see him.

Finishing The Job

By 9:00am, I was trying to locate another multi-coupler in New York to replace the one that failed. Unfortunately, there were none to be found, and one would have to be made. There was still the gain to the amp issue to be resolved, so after talking with LVS chief engineer Anzalone, he decided to wait till Monday when the new multi-coupler would arrive. However, city project manager Rogozin said he wanted the job finished now, by hook or by crook. So Anzalone joined the crew of Al Toledo and Ed Helpeck to spend Friday and Saturday finishing the job.

The job went along with many of the same difficulties, but in the end, the fire department and the city were very happy with the system’s capabilities and how well it worked. LVS’s Anzalone, Toledo and Helpeck are experienced professionals who worked in awful conditions to do a job that they wanted to do from their heart, not for a check. I feel privileged to have helped in the very small way that I did, with so many truly giving people, in this country’s largest disaster that happened in our backyard, New York City.

For more articles from Sound & Communications’ present and past, click here.