Editor’s Note: This month marks an important milestone for Peter Mapp, PhD, FASA, FAES, who took over the “Sound Advice” column back in 2008. This month’s offering is his 150th column. Congratulations, Peter, for delivering 150 informative, well-thought-out “Sound Advice” columns. Our readers and we look forward to many more!

Back in March, “Sound Advice” dealt with some practical issues concerning the measurement of the speech transmission index (STI) of a system. It was also noted that a new version (Edition 5) of International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) 60268-16, “The objective rating of speech intelligibility by speech transmission index,” had been published (September 2020). I thought it might be useful to go through some of the more significant changes within the standard that are particularly applicable to AV integrators and consultants, as well as to pick up on a few often-misunderstood points. The new standard replaces Edition 4, which came out in 2011. (Previous versions appeared in 2003, 1998 and 1988.) STI is now 50 years old, the concept having first been published in 1971 [Houtgast T and Steeneken HJM. “Evaluation of speech transmission channels by using artificial signals.” Acustica 25, 1971].

A Changing Standard

Each successive version of the standard has introduced technical improvements and refinements; the previous two revisions, in particular, have introduced concepts such as the effect of level-dependent masking and the effect of absolute sound level. In 2003, speech transmission index for public address (STIPA)—the faster and potentially portable measurement technique—was also introduced. The 2020 (Edition 5) version introduces a couple of new aspects, but, primarily, it ties up some loose ends and provides greater explanation of the concept and measurement practicalities. The most significant technical changes introduced by the new revision are as follows:

- The spectrum of the male-speech test signal has been changed, with significant reductions in the 125Hz and 250Hz bands being implemented.

- The female-speech test spectrum has been dropped, as the male spectrum gives a worst-case scenario and, often, there was confusion as to which one to use. Furthermore, the widely used STIPA method has never been verified for female speech.

- Details of the test loudspeaker (talk box) have been refined, with the maximum recommended driver diameter having been reduced from 100mm to 65mm so as better to replicate the sound field/directivity of a human talker.

- Several corrections to the underlying formulae have been made.

- Verification information for STI measurement devices has been added.

- The relationships between STI and several other speech-intelligibility measures have been updated.

- Greater information is provided about the adjustments to the measured STI results to simulate the effects of alternative noise and speech levels.

- The concept of “speech-shaped noise” has been added.

- The obsolete rapid speech transmission index (RASTI) method has been omitted.

- Four annexes have been added. These concern the following:

- Use of STI measurement devices (Annex D).

- Alternative direct methods for measuring full STI (Annex O).

- Information to be provided by manufacturers (Annex P).

- Effect of uncertainties of selected parameters on STI uncertainty (Annex Q).

It should be noted that Edition 5 replaces Edition 4, which is now effectively obsolete. (That being said, I suspect people will continue to use it for quite a while.)

Adjusting the Speech Spectrum

The most significant change to the standard is the adjustment to the speech spectrum. Its purpose is to bring the test spectrum more into alignment with recent research and other standards, such as American National Standards Institute (ANSI) S3.5.

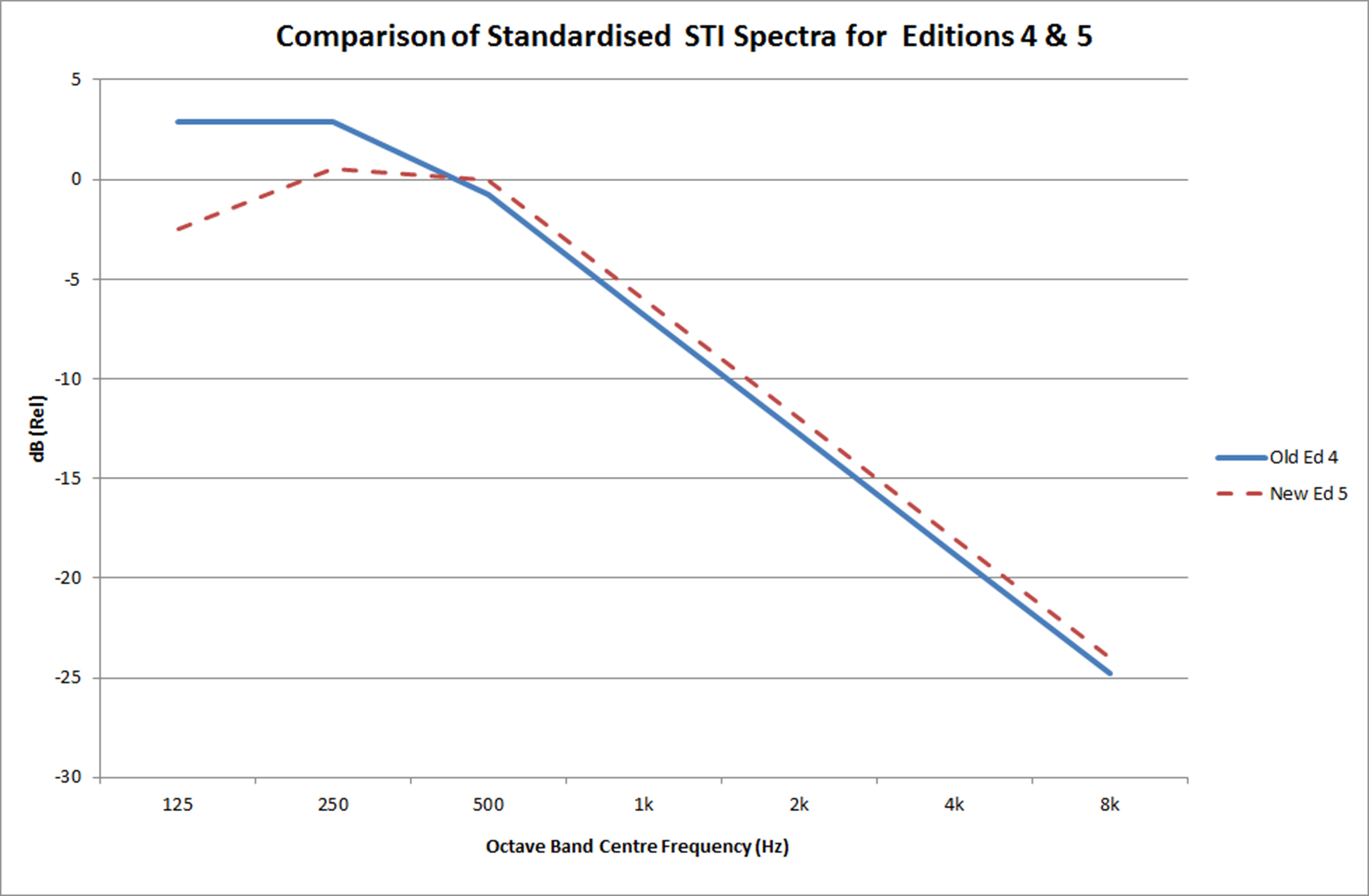

The best way to understand the changes is to look at Figure 1, in which I have compared the old and the new male spectrum. In essence, the level of the 125Hz band reduces by 5.4dB, whereas the 250Hz band level reduces by 2.4dB. These are quite appreciable changes, and they will considerably ease the burden that the old spectrum imposed on paging systems, emergency sound systems and communication systems in general that exhibit a limited low-frequency extension and performance.

Although these reductions in level are quite significant, the contribution (weighting) of these frequency bands to the overall STI is quite small; thus, there is little change to the overall measured (or predicted) STI value. Indeed, the standards team undertook extensive mathematical modeling to verify that the effect on the overall STI value would be minimal. An average error of just 0.01 STI resulted from approximately 1.4 million simulations with the new spectra. Therefore, in practice, no difference in measured values should be observed because of using the new versus the old versions (Edition 5 versus Edition 4) of the standard.

Normalized Equipment

A second change was the recommendation to use a talk box, or test loudspeaker, with a maximum driver diameter of 65mm, as opposed to 100mm. That is because it had been found that a 100mm (4-inch) driver exhibited significantly greater directivity than a human talker at high frequencies—and in the 2kHz and 4kHz bands, in particular. (Those are most important contributors to intelligibility.) The change primarily relates to acoustic measurements (e.g., the intelligibility of a talker in a room or space, or when measuring the performance of a system in which the talker is off axis to the microphone, such as with a ceiling or suspended microphone system). If the talker speaks directly on axis to a microphone and in close proximity to it, the directivity of the talk box is less important and 100mm drive units should still suffice.

One of the main objectives of the revision was to provide additional information to assist both the practitioner and the device manufacturer in understanding STI and its measurement. To that end, the standard has increased in size by around 50 percent, growing from 78 pages (71 pages of text) to 115 pages (107 pages of text). The significance of the updating is also perceptible in the increase in the number of cited references, which has grown from 49 to 58. Most of them relate to new research and findings that affect STI.

A further point to note when making STI measurements—this was introduced in Edition 4, but it’s often forgotten—is that the STIPA signal level must be set 3dBA higher than the speech level in order to be comparable. In other words, if a speech announcement level of 85dBA is employed (measured using either the “slow” weighting or LAeq), then the STIPA signal level must be set to 88dBA in order to be equivalent and provide an accurate assessment.

To read more from Sound & Communications, click here.